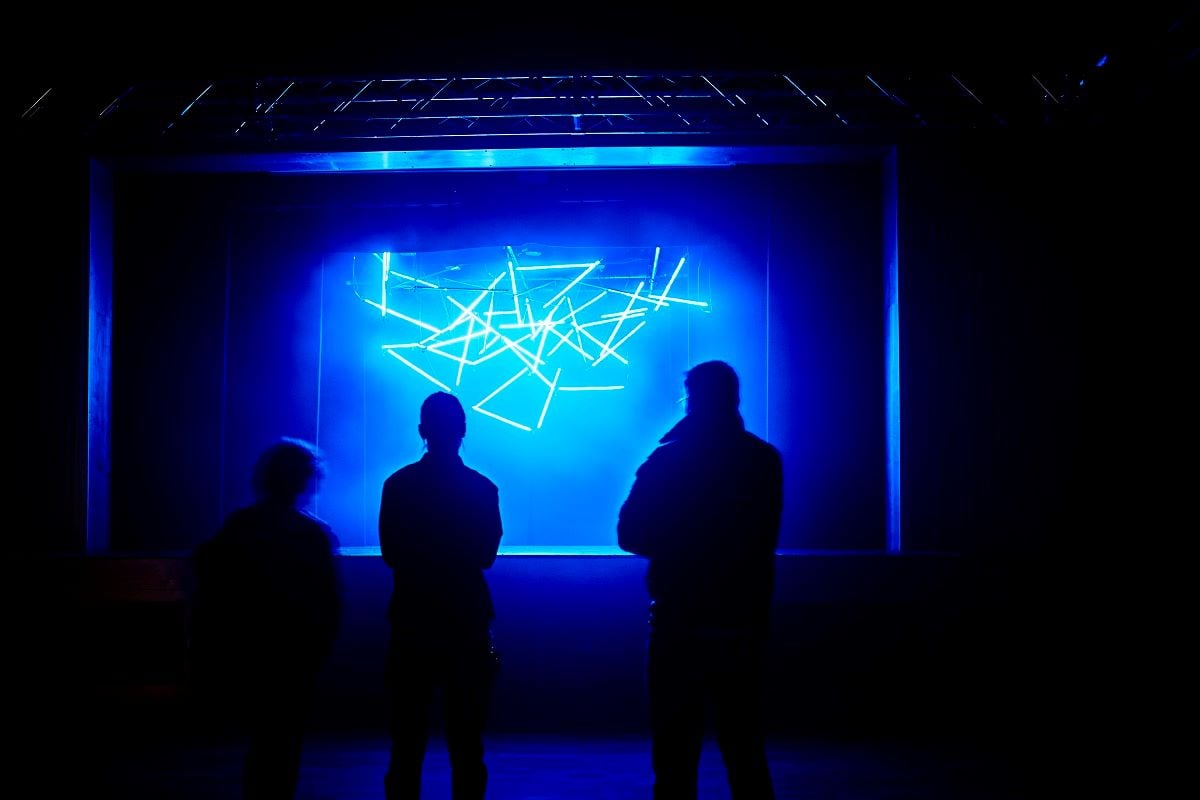

Light Night at the University of Leeds

Photo: University of Leeds

Why better data is vital for future-proofing the cultural sector

Why do we struggle to convey the cultural sector’s significant impact? There’s no easy answer but an obvious solution lies in harnessing quantitative and qualitative data, argues Ben Walmsley.

The Centre for Cultural Value (the Centre) recently led a national, interdisciplinary research project aimed at tackling the crisis the cultural sector is facing in harnessing and evaluating its data. In doing so, we quickly discovered a paradox.

In the UK, we are lucky to have one of the highest volumes of cultural sector data in the world. Yet, many organisations reported they still didn’t have the time, capacity or skills to analyse and use their data strategically.

Through this work, it also became clear that even our well-resourced national organisations do not always know what is expected of them regarding data. In addition, there is no one-stop shop for collecting and sharing data – making learning difficult within and across organisations.

In fact, in our final Making Data Work report we detailed a fragmented national picture; organisations were swimming in data, but they did not always know what to do with it or even why they were collecting it.

All of this led us to ask: how can we collect smarter and more ethical data to tell the nuanced story of why arts and culture matter?

Why data matters

Our research on the impacts of Covid-19 highlighted the vital role of culture for the nation's wellbeing during a time of crisis. Now, amid a cost-of-living crisis and with a protracted recession looming, it is more important than ever to draw on robust data to demonstrate the diverse impacts of culture.

When budgets are at risk of being squeezed, our data can help us make the evidenced case for why arts and culture shouldn't slip down the priority list of governments, funders and philanthropists. Furthermore, as cultural activity becomes more aligned with health and well-being and educational outcomes, we increasingly need to understand who is – and who isn't – engaging with that activity and why.

It is also the case that better data can be used to inform and evaluate policy at a national level. With at least 15% of Arts Council England (ACE) funding now being redistributed out of London, we need data to track and understand if this change has led to the desired outcomes in addressing regional inequalities.

It is therefore notable that, at a time when we need data to answer these big questions, organisations who have to date been key to supporting the sector in this area have seen their ACE funding reduced. This raises the question: how do we now champion the cause of open cultural data and a sector confident and able to use it?

An appetite for innovation

In undertaking the Making Data Work project, we worked with arm’s length bodies to understand what the sector needed in terms of skills development, data standardisation and ethical data management.

What became apparent was the need for a new, systematic approach. We therefore developed a multidimensional evaluation framework in collaboration with Jonothan Neelands at the University of Warwick, and Beatriz Garcia, Associate Director at the Centre. We wanted to see how we could use creative methods to capture qualitative data, combining this with quantitative datasets to convey the holistic impact of cultural activity.

As part of our case study in Bradford, we encountered real excitement from cultural organisations and local government about engaging in creative data collection methods. Again, the barriers were a lack of infrastructure and time. However, our experience demonstrated that, if invested in and supported properly, real potential exists in the sector to use data to build a nuanced picture of cultural value in ways that are sensitive to and reflect creative activity itself.

Next steps

The Centre is now calling for the establishment of a national observatory for cultural sector data, where specialists in the field can bring together, research and analyse mixed data sets.

We also believe it is vital that the sector builds on its strengths and skills in data collection and management. Of course, this comes with challenges: organisations currently face a turbulent time, with some referring to a ‘permacrisis’. Confronted by an economic recession, it might seem appropriate to cut supporting functions such as audience insight and data teams, and instead prioritise core activity.

However, by taking the opportunity to invest in smarter data capture and analysis, organisations will be better placed to make their case in the long term. It is only by understanding who they are engaging and the value of that engagement that organisations can best serve their audiences, understand their impact, adapt to change and be prepared to deal with future crises.

As with the Centre's suggested approach towards evaluation, perhaps the key to data management is to do less better. By following this approach, the UK cultural sector will be well-placed to retain its leadership in audience research and insight.

You can read the executive summary and the full Making Data Work report on our website, including our recommendations for next steps.

Keen to stay involved in the conversation about the role of data in the cultural sector? Sign up for our newsletter to hear about our future work in this field. We'd also be eager to hear your questions, thoughts and comments about making data work for the sector. Please get in touch with us at [email protected].

Ben Walmsley is Professor of Cultural Engagement at the University of Leeds and Director of the Centre for Cultural Value.

![]() www.culturalvalue.org.uk

www.culturalvalue.org.uk

![]() @BenWalmsley | @valuingculture

@BenWalmsley | @valuingculture

The Making Data Work research team comprised researchers from arts management, cultural policy, psychology and quantitative sociology, working closely with industry experts from The Audience Agency and MyCake.

We wish to thank our project funders, the Economic and Social Research Council, and the Centre’s three core funders for providing the infrastructure that made this research possible in the first place: the Arts and Humanities Research Council, Arts Council England and Paul Hamlyn Foundation.

This article, sponsored and contributed by the Centre for Cultural Value, is part of a series supporting an evidence-based approach to examining the impacts of arts, culture and heritage on people and society.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.