Photo: woodleywonderworks on Flickr (CC BY 2.0)

Bridging the academic-classroom divide

Music educators often lack the confidence and energy to engage with academic research. Encouraging them to do so may be the way to address the disconnect between the two worlds, argues Dr Steven Berryman.

Educators’ confidence to interact with academic literature is thriving on social media, with a growing number of blogs, articles and books that champion ‘what the research says’ and how it plays out in classrooms. But when it comes to music education, the work of academics is dislocated from the reality in the field: the British Journal of Music Education was ranked 238 out of 263 in education research in 2019 and its articles typically have low numbers of readers and citations. With the metrics visible on the journal website, we have an accurate picture of access to online articles over the past 12 months, which is tiny when you consider the size of the music education workforce.

Two worlds

As an educator who has worked from primary through to postgraduate, I felt well positioned to consider how might we increase dialogue across the academic-classroom divide and build relationships across these distinct communities. We need to speak a common language, to be able to address shared concerns, and feel heard. The debates that play out on social media suggest those academics and educators share the same fundamental aspirations but different priorities. From many years working in music education, I know that classroom educators can lack confidence to engage with academic literature and may feel intimidated by academic expertise – not to mention the paywalls that prevent access for those outside of higher education.

The idea for a blogging project with the British Journal of Music Education (BJME) came about following a tweet in which I curated a list of articles from the journal for teachers to read and reflect on. BJME’s editors were quick to offer their support; together we selected 11 articles including a focus article each week. Teachers could read them and share their responses with me, which were then gathered into a single post that we shared with music education platform, Music ED UK. We chose articles on issues we felt were pertinent now: inclusivity, priorities in teaching, and wellbeing in music making.

Professor Martin Fautley, co-editor of BJME, was a generous supporter of the venture. He understood that one of the common criticisms levelled at academic publishing is that it is inaccessible to teachers who are far too busy with the day-to-day to read it anyway. Despite the pressures on their time during the pandemic, music educators welcomed the opportunity to connect with peers and sustain their professional learning. David House, a participant in the project, said this type of reflective engagement was worth more than many courses and enabled him to communicate with fellow teachers near and far.

Real impact

The project built on a previous collective blogging project I delivered during the first national lockdown in the UK; it was more ambitious in that we blogged every day, which was too demanding! Teachers were losing the energy to keep contributing. Our BJME project worked much more effectively. It was a coherent set of articles from one journal paced to fit with teachers’ lives (one article per week with the whole set shared in advance) and published over 11 weeks. BJME made the articles open access for one year to remove any barriers to engagement.

We have completed the project now and all responses and links to the articles can be found on Music ED UK. I asked the editors of BJME to reflect on their experience of the project. Dr Ally Daubney said it “offered teachers a series of stimuli through which to reflect and reimagine music teaching and learning in their own context, and in this constantly evolving world”. House, the participant quoted earlier, shared Ally’s enthusiasm for the venture: “This project chimes so well with the need for all music teachers to engage thoughtfully throughout their careers.”

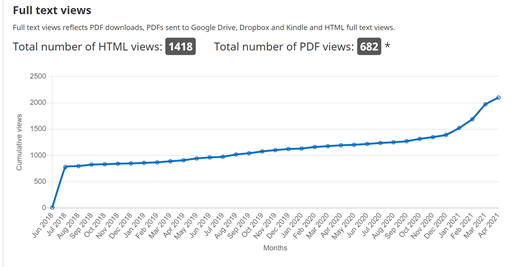

Looking through the articles featured in the project, you can see that viewing numbers increased over its duration. This is thrilling; it demonstrates a snowball effect to building educators’ confidence to access and engage with academic literature. From a three-year high of 1500 views in January, readership spiked in the early months of the year to reach more than 2000 by April.

Genuine appetite for engagement

The posts created by the teachers’ responses received over 5,000 views over the project’s short lifetime. It is clear there is a genuine appetite to engage with academic literature by arts educators. If journals are willing to work with their subject associations, perhaps more blogging projects of this kind are possible.

This model is simple to instigate, and while we had nearly 50 teachers involved in writing responses, my role in compiling them was achievable. Academic publishers might consider reaching out to subject and professional associations relevant to their field; this blogging project is easily replicable and could serve as a model for academic publishers to engage with artists more generally. Building access and a conversation around published articles furthers key debates in the sector, but most importantly it builds a bridge between sectors that exist to enhance our aspirations and build a better world.

Dr Steven Berryman is Director of Arts and Culture for the Odyssey Trust for Education, a Visiting Research Fellow at King’s College London and Guildhall School and Curriculum Lead for the Music Teachers Association.

![]() steven-berryman.com

steven-berryman.com

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.