Photo: Wachiwit

A framework for failure

The cultural sector is not given to discussing failure – a common problem across much of public policy. But here Leila Jancovich and David Stevenson argue much can be learned from acknowledging it.

Previously in these pages we have argued that the cultural sector has a problem talking about failure. This has been informed by our research* which involved workshops, interviews and online surveys with participants in the cultural sector, both paid professionals and voluntary participants.

We identified that the precarious nature of work in the sector makes many professionals fear that talking openly and honestly about failure might jeopardise their chances of securing future funding or employment. Furthermore, the concern with constantly ‘evidencing’ the ‘value’ of cultural organisations and projects, often to justify public funding, results in a tendency to conflate success with value.

However, just because a cultural project fails to deliver desired outcomes does not mean it lacks value. Likewise, in celebrating the value of cultural projects we should not ignore failures nor miss the opportunity to understand why they happened and reflect on what could be done to minimise the chances of repeating them.

The need for honesty

If the stated aims of cultural projects do matter, there is a moral imperative to learn about if, where and for whom such projects may have failed. This is not about apportioning blame. Rather, it is about recognising that, if there is a genuine desire to change existing patterns of participation, to diversify decision-making voices and to expand the breadth of activities and organisations recognised and supported as culturally valuable, these goals will not be achieved by ignoring failures. Nor by avoiding difficult decisions in favour of sharing feel-good narratives that defend the status quo.

Lots of work in the cultural sector addresses significant and complex societal problems so failures are to be expected. Cultural projects can deliver amazing outcomes on modest budgets but they often achieve less than hoped for. We need to be honest about the limitations of what current practice is achieving and to openly discuss what, if anything, can be done to change this.

Creating truly accessible events is difficult – some access or language needs may not be met because of the size of the budget, the limitations of the venue or a lack of experience of those involved. When evaluating such projects, we need to acknowledge these failures, even when there is no obvious solution. Only by making failures consistently visible can we collectively find ways to address them.

Success and failure coexist

Throughout our research we found policymakers, practitioners and participants defined success and failure very differently – but rarely shared this uncomfortable fact. This diversity of perspective and experience highlights the fact that success and failure coexist. So the first step towards a more critically reflective cultural sector is for everyone involved in the design, delivery and evaluation of policies and projects to acknowledge that failures do happen and to normalise talking honestly about them when they do.

We recognise that is difficult, especially if there is a pre-existing lack of trust between stakeholders. Discussions about failure can feel judgemental and the defensiveness this engenders is not conducive to open dialogue.

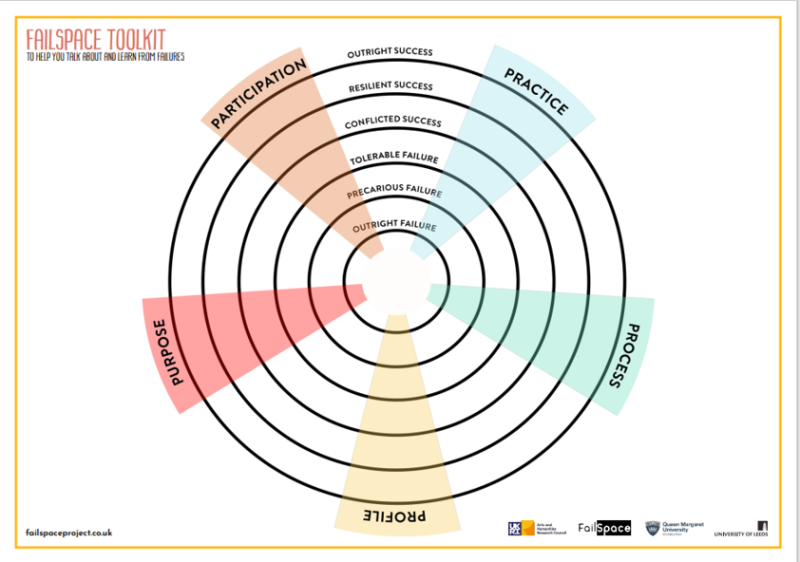

For this reason, we have developed a framework that moves beyond the false binary of success versus failure to encourage a more critically reflective discussion about how cultural projects succeed and fail simultaneously, in different elements of the work, to differing degrees, at different stages, and for different people in different ways.

Facets of success

The framework includes five facets of success and failure, each of which must be considered separately along a scale from outright success to outright failure. We offer the framework as a method for having difficult conversations in a structured way and employing language that allows for a more nuanced account of where failures may have occurred. It is intended for use at the project outset, throughout its delivery and as part of the evaluation.

More detail can be found about the framework in our book, Failures in Cultural Participation, but we have been pleased with the responses from those who have engaged with it so far.

More detail can be found about the framework in our book, Failures in Cultural Participation, but we have been pleased with the responses from those who have engaged with it so far.

Some 1,000 cultural professionals have taken part in workshops with many saying they found it cathartic to talk about what failure might look like before starting a new project. However, when it comes to the end of a project, most people still default to talking about successes.

Likewise, while many were keen to use the framework for self-reflection, there was resistance to acknowledging failures publicly, especially with funders. This despite the fact that all the funders we spoke to accepted there would be failures in the work they funded.

Moving towards sustained change

Our own failures to date in terms of engendering sustained change in professional practice is perhaps indicative of how difficult it will be for the cultural sector to move towards more open and honest conversations about failures: failures that have limited and continue to limit progress towards greater cultural equity.

In reflecting on our own project’s failures, we recognise the need for a greater focus on encouraging others to take the framework and make it their own. This would maximise the chances of its continuing use after the project ends.

To this end, we have recruited champions from the sector to disseminate our work and we are collaborating with funding partners to explore ways they might better encourage those they fund to acknowledge, report and learn from failures.

These findings will be shared at a national conference, Failspace, being held next week where our partners and champions will share the platform with contributors from academia and the cultural sector.

We invite everyone who cares about the cultural sector to join us for a day of panels, discussions and workshops that critically examine the role failure – and conversations around failure – can play in making the sector more honest, critically reflective and ultimately more equitable.

Leila Jancovich is Professor of Cultural Policy and Participation at the University of Leeds and an Associate Director of the Centre for Cultural Value.

David Stevenson is Professor of Arts Management and Cultural Policy at Queen Margaret University, Edinburgh and an Associate Director of the Centre for Cultural Value.

![]() @LeilaJancovich | @PCI_UniofLeeds | @mrdjstevenson | @FailSpaceProj

@LeilaJancovich | @PCI_UniofLeeds | @mrdjstevenson | @FailSpaceProj

![]() www.failspaceproject.co.uk

www.failspaceproject.co.uk

Sign up for for: Failspace: How the cultural sector can learn better from failures.

*Failspace – also known as Cultural Participation: Stories of Success, Histories of Failure was funded by the Arts and Humanities Research Council.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.