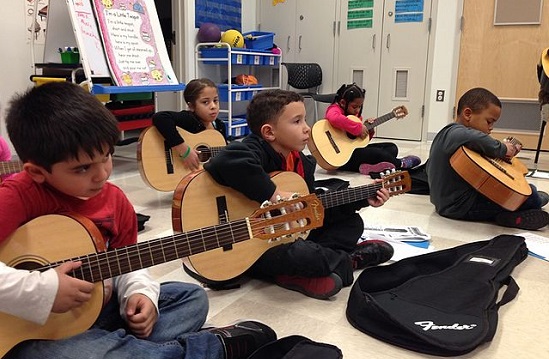

Music can improve children's numeracy through counting and reading through the familiarity of syllabic patterns

Photo: www.tradenews.sg

What makes an ‘arts-rich’ school?

Two West Yorkshire schools decided to put the arts at the heart of their curriculum. They found different challenges – but had similar successes.

Specialist teachers, dedicated arts spaces and partnerships with local and national arts organisations are key to creating a successful “arts-rich” school, according to a social change organisation.

The Royal Society of Arts, Manufacturers and Commerce (RSA) identified 46 “art-rich” British schools that prioritised teaching a broad range of arts subjects or had a highly-developed, arts-based pedagogy shaping their curriculum: “In practice, these were often found together.”

But schools’ abilities to develop students’ cultural capital – and prove the benefits of doing so – are being squeezed by “the national accountability regime”, which values on-paper results more than intangible improvements, the society’s research report says.

READ MORE:

- EXCLUSIVE: Arts in schools plummets, figures show

- No school ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ without arts, says ACE

RSA interviewed 24 schools, visiting nine of them to better understand the value of an arts-based education and find out “what enables and motivates some schools to place the arts at the heart of the learning”.

While different circumstances triggered individual schools’ investment in the arts – relocation, new government investment, the arrival of staff with passion and skills in the arts, poor Ofsted evaluations or exams results, or a desire to differentiate the school from its competitors – the research identified several practices common to arts-rich schools.

|

What is an arts-rich education? Arts-rich schools … Actively encourage students to take arts subjects Equip and maintain arts facilities Ensure their budgets reflect the cost of arts teaching Include the arts and cultural sectors in careers advice Partner with local and national arts organisations Have teachers undertake arts-related development Subsidise excursions, visits and performances Offer arts clubs, lunchtime and after school activities |

Gomersal Primary School

Gomersal Primary School’s art room is large and bright, with colourful artwork adorning the walls and fresh creations in drying racks scattered around the room. Students using the once-neglected space told the visiting RSA researchers that Maths and English are “important, but not the only thing that matters”.

The room is “a benefit but not an essential ingredient” to Gomersal’s success as an arts-rich school, according to its specialist art teacher Mandy Barrett.

A poor Ofsted result in 2016 “sparked an intensive school improvement process,” RSA’s report says. New headteacher Melanie Cox decided to put the arts at the heart of the school: pupils have at least one full morning or afternoon of arts time per week, teachers receive arts-focussed professional development and perform arts outreach with other schools, and the school has an active Student Arts Council that suggests improvements.

|

Delivering an arts-rich education: Important steps include … Giving the arts a high status Creating dedicated arts spaces Developing a range of partnerships Having specialist arts teachers at primary schools Maintaining curriculum breadth at secondary schools Timetabling the arts so they are central to school life |

A skills audit “unearthed hidden talents among [the] staff”. A cover supervisor who runs her own performance company now leads’s Gomersal’s performing arts programme two afternoons per week, while its dedicated ‘Arts Link Governor’ is using skills and resources from his radio and producing career to improve the school’s music offer.

Last year, Gomersal was shortlisted for Creative Schools of the Year in the TES Schools Awards. Its Ofsted inspection report – up from ‘Requires Improvement’ to ‘Good’ – noted that “the good quality of the curriculum and visits into the wider community contribute well to developing pupils’ spiritual, social, moral and cultural understanding”.

School staff told RSA that “within the pressurised context of a Requires Improvement judgement, it can feel like a risk to go against the grain in taking an arts focus”.

Cox said that focus has contributed to students’ increased confidence, wellbeing and sense of identity, but is hard to evidence the value of those gains to officials: “it’s one of those immeasurable things. And that’s the difficulty, isn’t it? How to measure it.”

Feversham Primary Academy

RSA’s report points to Feversham Primary Academy as illustrating a possible solution for educators trying to evaluate the impact of the arts: “[This] school notably bucks the trend and may chart a way forward for other schools who wish to understand how their arts practice can make the greatest difference to pupils.”

Feversham and its headteacher, Naveed Idrees, have garnered media interest in recent years for crediting its remarkable turnaround from ‘Special Measures’ to ‘Outstanding’ to its investment in music teaching. Idrees explained that the school, situated in one of the country’s most deprived neighbourhoods, has “the same children, same teachers and same community and because of the arts-based curriculum, it’s now in the top 2% of the country” for progress in English and Maths.

Its pupils receive three music lessons per week, paid lessons in piano, drum, trumpet or guitar, lunchtime and after-school music clubs, a weekly music assembly and three music-based ‘enhancements’ per pupil, per term – one local, one in the wider community, and one visitor to the school.

Feversham uses the Kodaly Method, a pedagogical approach that uses exercises and games based on rhythm, singing and folk songs. This technique, which has been linked to improving reading, numeracy and IQ test scores, requires a trained practitioner but few other additional costs.

The method is used across Feversham: its staff told visiting researchers that they have adopted some of the cues used in music lessons in their classes, for example to prompt students to pay attention or sit down.

RSA concluded: “In general, if schools draw on existing research to make choices about what arts practice to offer, they can be more confident that they will see the impact they expect.”

The paradox

The research notes a conundrum in current expectations around education, saying “school leaders face competing demands from the national accountability regime”.

Secondary schools must aims for 75% of their pupils to be studying a combination of English Baccalaureate (EBacc) subjects at GCSE by 2022, and 90% by 2025.

“On the other hand, they must demonstrate to Ofsted how they are developing pupil’s cultural capital. The former does not include the arts, the latter seems impossible to achieve without them.”

RSA’s report does not make specific recommendations for schools or education officials: “there is no silver bullet.

“However, we think that the stories of the schools featured in this report offer some inspiration. In spite of the changing funding and accountability context, these schools have steadfastly committed to the arts.

“In doing so, they have consistently delivered curriculum breadth and cultural capital to their pupils. As the report demonstrates, this requires dedication, effort, and – sometimes – difficult choices.”

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.