The disadvantage for disabled working-class individuals is three times that of their abled-bodied peers of privilege

People with privileged pasts twice as likely to hold creative jobs, study finds

New research finds that social mobility is "a greater issue for the creative industries than across the wider economy" – and a pressing concern amid the pandemic.

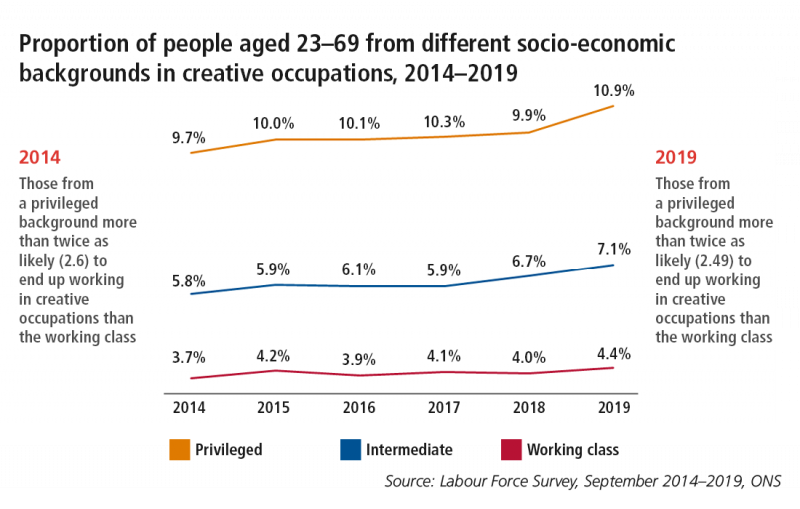

People from privileged backgrounds are twice as likely to work in creative jobs as those from the working classes.

The finding by the Creative Industries Policy and Evidence Centre (PEC) illustrates the sector's entrenched problem with social mobility, which researchers said is being acknowledged but remains poorly understood.

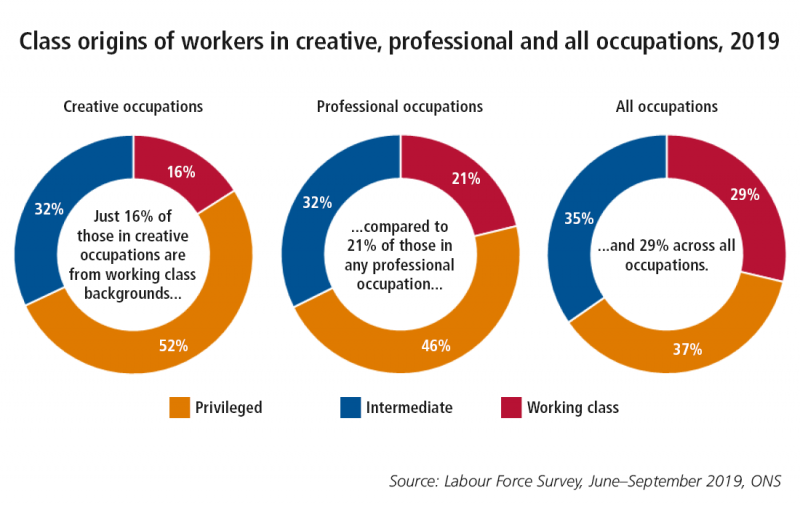

Using Labour Force Survey data and socio-economic occupation codes, the study determined that people from working class origins comprise about a third of the UK's population, but just 16% of the creative industries' workforce.

READ MORE:

- Working classes 'significantly excluded' from arts careers

- Can a toolkit solve the arts sector's class problem?

Attempts to address the imbalance have had little effect: the likelihood of someone from the working classes finding creative work has grown by just 1.4% in five years – a shift that may be more emblematic of a historic decline in working class professions than real change.

"The fact we are seeing very little shift in the make-up of the creative workforce suggests our efforts to date are falling short," the research report says.

"We are not starting from a blank canvas… But while we have a range of ideas and in some cases evidence on the factors that influence an individual’s fate when looking to work and progress in the creative industries, we lack a coherent narrative about the scale and nature of their impact; which are most important and why.

"When compared to the picture of social mobility into professional and managerial occupations in other sectors, the data suggests social mobility is a greater issue for the creative industries than across the wider economy."

Double disadvantage

As the pandemic leads to more job losses, "we should expect those who are already marginalised to be worst hit," the report says.

Researchers found a "double disadvantage" where class intersected with other protected characteristics: for example, someone from a privileged background who is university educated is more than five times as likely to work in the creative industries as a working class person with a GCSE-level education.

Women, who are already underrepresented in the creative industries, are nearly five times less likely to secure a job than men from privileged backgrounds if they have working class origins.

People with disabilities are 20 to 30% less likely to land a creative role than their non-disabled peers. But if a working-class disabled person is pitted against a non-disabled worker of privilege, the disadvantage rockets to 300%.

Heather Carey, PEC Co-Investigator and Director of Work Advance, said the pandemic has "only served to emphasise the vulnerabilities" inherent in policies and programmes aimed at addressing class disparities.

The PEC will conduct further research to better understand the role class plays in specific sub-sectors and occupations in the creative industries.

"As we look to rebuild the sector, now is the time to consider how we can address long-standing structural weaknesses," Carey said.

Every sector (except crafts)

The research says "what is striking is that, with the exception of crafts, class imbalances exist across every creative industry".

Publishing and architecture had "the most pronounced and enduring" class divide over the five years to 2019, drawing between 42 and 65% of its workforces from privileged backgrounds.

But music and the performing and visual arts were little better. Classed as one sector in PEC's research, their working class cohort averaged just 12%.

Crafts bucks the trend, with about one-third of the sector coming from the working classes compared to 28% from privilege.

The remaining 40% are from the 'intermediate classes', which PEC defines as people whose parents worked in lower supervisory and technical jobs, or were self employed.

On autonomy

Getting into the creative industries is just half the battle: PEC's research found that workers with privileged pasts experienced more autonomy over their job and working hours than their working class peers.

They were also more likely to be managers and supervisors by a margin of 10 percentage points.

There is perhaps a silver lining in that creatives were found to have more autonomy than people working in other sectors.

But the findings "offer little in the way of reassurance for those concerned that talented individuals from working-class origin might make it into the occupations that include our curators, or authors, our musicians, artists, actors and entertainers, and our film-makers," the report says.

"The issue does not end with whether or not those from a working-class background can make it into our creative industries, but rather whether they are able to thrive and progress once there."

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.