The value of creative thinking

What exactly do we mean by creativity, and how will the UK measure up when the world education league tables start assessing it in 2021? Bill Lucas examines the evidence.

In 2021, the Programme for International Student Assessment (PISA), which tests a sample of 15-year-olds across the world every three years, will include an assessment of creative thinking. For the last two years I have been working with the team developing this new test at the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD).

Arts professionals, teachers, parents, students and employers should be up in arms about the unwarranted narrowing of the school experience

That it will be included alongside the more well-known tests of maths, science and reading is a huge boost in status to a topic that, although increasingly valued globally, is not yet seen as important enough in the English education system.

Creative thinking and creativity

Creative thinking is what you do when you are being creative, and creativity is the outcome of this. The study of creativity is some 70 years old and most researchers trace its beginnings to the work of Joy Paul Guilford in the middle of the last century. Guilford suggested that there are two kinds of thinking: convergent (coming up with one good idea) and divergent (generating multiple solutions).

Building on this line of thought, Ellis Paul Torrance developed four sub-categories: fluency, flexibility, originality and elaboration. More recently, Robert Sternberg has argued that creativity is three-dimensional. It requires synthesising (the ability to see problems in new ways and escape from conventional thinking), analysing (being able to recognise which ideas are worth pursing and which are not), and contextualising (having the skills in different settings to persuade others of the value of any specific idea).

Creative thinking is both a solo and a collective activity, and most often has a social component. Creativity can be viewed as domain-specific (being creative in science, for example) or domain-free (being creative in any situation). Anna Craft reminds us that while only a few may aspire to be an exceptional genius, all of us can show a more ordinary form of creative thinking that she termed ‘little c creativity’.

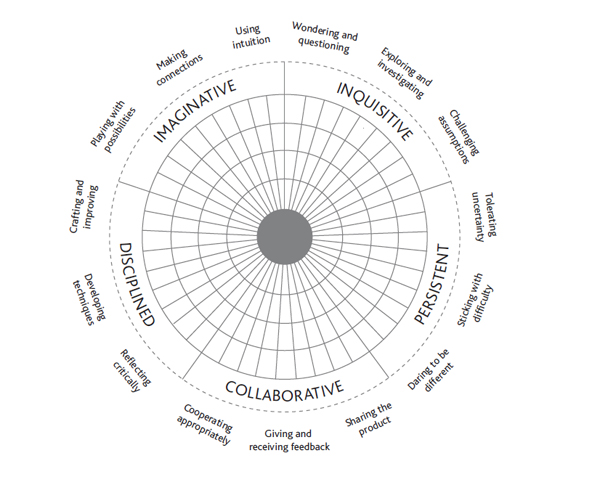

With my colleagues at the Centre for Real-World Learning, I have developed a five-dimensional model of creativity.

The five-dimensional model of creative thinking

A creative education

A creative education is one in which schools provide ample opportunities for young people to develop all the elements of this model through the formal curriculum, in after-school activities and in the school’s wider community role. In creative schools there is a clear message that, while not all pupils can be world-class dancers, makers or players, all can develop their small c creativity in ways which will help them to thrive and grow, and enjoy their own emerging creativity.

Working with schools across the world we are now able to show how certain kinds of teaching and learning are likely to foster creativity. These include the use of case studies, problem-based learning, an approach known as philosophy for children, role play, games, deep questions to which there are no easy answers, authentic tasks, peer teaching, self-managed projects and enquiry-led teaching.

Most of these shorthand descriptions are self-explanatory or at least indicative of their intent. They have one in thing in common: they seek to harness young people’s imagination and curiosity to develop, rehearse, practise, shape, redraft, critique and re-conceive their ideas in response to a range of different stimuli and in many different contexts.

For many people, the arts – music, art, design, dance, drama, literature and so forth – are synonymous with creativity. But creativity is actually much bigger than even these important subjects. It is to be found in every subject on a school curriculum and in every facet of our lives. It is as much about the unravelling of the human genome as it is the composing of a piece of music, as present in the hadron collider in Cern as in street theatre.

Nevertheless, the arts have a contribution to make to creativity specifically and to education and life more generally. The arts offer a specific way of knowing about and being in the world. When we use our imagination, we make new connections, see and feel things differently and develop our own humanity. We can expand our horizons without actually moving from where we are. The arts are a critically important part of any civilised education.

Dwindling numbers

Right now in schools in England they are under threat. The Cultural Learning Alliance has charted the dramatic (pun intended) reduction in numbers of students studying arts subjects at GCSE from 673,739 in 2010 to 435, 784 in 2018. These are shocking statistics. While art is just about holding up, design and technology, dance and performing arts have suffered huge reductions between 45% and 63%. The Department for Education’s own statistics, published this June, show a reduction of 21% in the hours of arts teaching in schools and a reduction of 20% in the number of arts teachers.

Arts professionals, teachers, parents, students and employers should be up in arms about the unwarranted narrowing of the school experience. It is worth reminding ourselves of Article 22 of the UN Declaration of Human Rights that states that mankind is ‘entitled to realisation of the economic, social and cultural rights indispensable for his dignity and the free development of his personality’. The Convention on the Rights of the Child (Article 31) talks of the right of the child to participate fully in cultural and artistic life.

In many primary schools there are no specialist arts teachers. In secondary schools the EBacc’s emphasis on so-called academic subjects is squeezing out both the arts and other practical subjects.

Bang the drum

But all is not lost. As well as the promise of enhanced status through PISA, there are thousands of arts professionals, creative practitioners and curious scientists working in schools. In Wales, to take one example of promising practice, more than 500 schools are working with the Arts Council of Wales, the Welsh government and Creativity, Culture and Education to explore aspects of our model of creativity.

Or at the level of policy, the Durham Commission for Creativity in Education, led by Sir Nicholas Serota, is consulting widely with many stakeholders about the multiple benefits of creativity in schools, with a view to laying out a compelling agenda for creative change.

Whatever your role in schools, whether an arts professional or a parent or both, I strongly urge you to bang the drum for creative learning and for the arts in any school to which you are connected.

Bill Lucas is Professor of Learning at the University of Winchester. He is Co-chair of the PISA 2021 Test of Creative Thinking and an academic adviser to Arts Council England on creativity in education. He is also the academic adviser on creativity to the 14-18 NOW WW1 Centenary Art Commissions.

www.winchester.ac.uk

Bill Lucas and Ellen Spencer are authors of ‘Teaching Creative Thinking: Developing learners who generate ideas and can think critically’.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.