Photo: Max van den Oetelaar on Unsplash

Planning in a time of radical uncertainty

In these uncertain times, it’s important to return to our core principles: making the most of the information we have and not being afraid to experiment, explains David Reece.

I’ve just finished reading Radical Uncertainty: Decision-making for an unknowable future, in which Mervyn King and John Kay assert that decision making today is too reliant on predictive models that “claim knowledge of the future that we do not have and never could”. Given King ran the Bank of England for 10 years and Kay is one of Britain’s leading economists, there’s something reassuring about the fact that even they don’t claim to know the future.

But that doesn’t mean planning for future events is a waste of time. We must still make decisions, allocate resources, and plan for possible scenarios. Effective forecasting is not about saying this is what will happen, but rather what might happen. While what might happen involves endless possibilities, as King and Kay argue, we should look for strong “reference narratives” to deal with uncertainty.

Scenario planning

Let’s ask an essential question for any situation: “what is going on here?” Scenario planning means making the best use of the information you have and considering the circumstances under which events might unfold. Coronavirus is not going away anytime soon. Several potential vaccines look promising but even a vaccine, however effective, is not a silver bullet. For now, we have to continue to live with the virus. But what does that mean for the cultural industry?

A recent AEA Consulting report based on interviews with more than 160 arts leaders and experts in the US presents potential scenarios for the industry in light of Covid-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement.

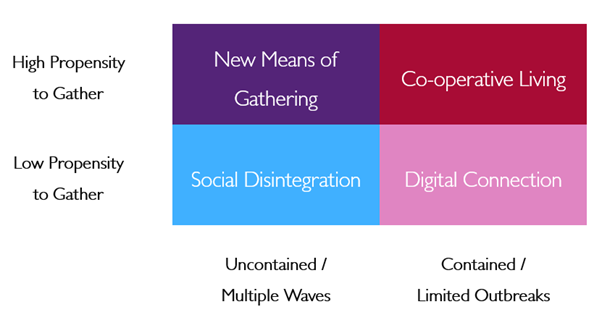

The landscape in 2021 and beyond is considered in relation to two factors: the severity of the pandemic and the social response to it. These may result in co-operative living, where there is a high propensity to gather and outbreaks are contained, or social disintegration due to low propensity to gather and uncontained outbreaks. Thinking in this way provides a useful framework for considering possible futures without plotting out an overwhelming number of narratives.

The situation we are most likely to face will be unlike anything we have experienced in the past. Simply throwing out the past would be a mistake, though. A. G. Lafley and Roger Martin write in Playing to Win that we shouldn’t “allow what’s urgent to crowd out what’s really important”. The crisis might be playing havoc with ‘business as usual’, but arts organisations are often the most creative, flexible and determined businesses in the world. This robust sense of purpose can provide a set of guiding principles for decision making that extend across everything you do.

Of course, guiding principles are only part of the process; you must also clearly diagnose the problem and understand the situation at hand. You must focus your efforts where they make the most difference – and audiences are a great place to start.

Listen carefully

Our work as part of the Insights Alliance, producing the UK-wide Culture Restart sentiment tracker, found at least 58% of core customers would consider returning right now if appropriate safety measures were in place. Communicating and engaging with customers is crucial in any scenario, but in the short- to medium-term, two types of customer will draw greater focus: local communities that can access venues amid travel restrictions and digital audiences. Amid a drop in international tourists – and tourist spending – appealing to local audiences becomes a matter of necessity.

While in-person audiences might turn more to the local, digital can reach a much wider audience. Recent studies into audiences for digital theatre revealed 43% of digital audiences in the US were new to organisations’ databases, while international reach for a UK-based Zoom production was up to 17% across 27 countries, compared to 7% across 11 countries hosting the live show in 2019. One of the key findings from both studies was that willingness to pay for digital content was lower among new audiences and those unfamiliar with digital, but willingness to pay post-viewing increased – after they experienced the value.

Determining value

In a world of restricted-capacity, in-person events and increasing reliance on digital content, understanding what customers value, and more importantly what they’re willing to pay for, is key to maximising your earned income. It might not be what you expect: some of our recent research found people are willing to pay close to pre-Covid prices for reduced-length concerts with no interval in a socially distanced auditorium. The length of a concert is not necessarily associated with the value of the experience.

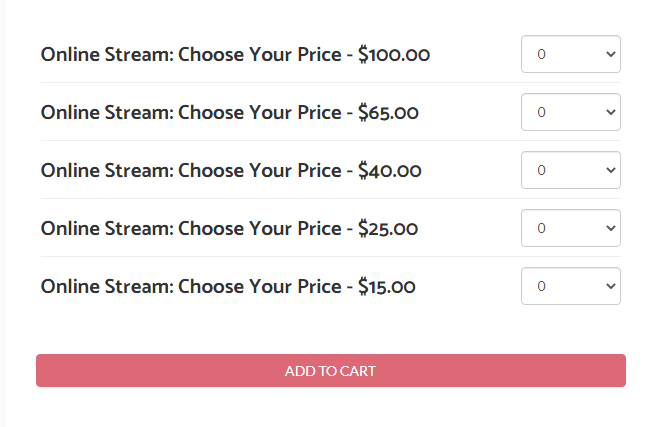

While digital as a viable revenue stream is still in its infancy, the principles of an in-person pricing strategy still apply. You must offer multiple price points to suit customers’ varying degrees of willingness to pay. Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony, for example, let you “choose your price based on your current situation”. They suggest: “When selecting your price, you might consider how many people in your household will be watching the stream, and what you might usually spend on attending a concert”.

(Screenshot / Kitchener-Waterloo Symphony)

By October 15, they generated $20,000 more than if they had offered a single price point, while maintaining a low, accessible price of $15, which 25% of their audience purchased.

Experiment and invest

Knowing where to invest to create value continues to be a moving feast, which is why experimentation with technology and institutions is so important. We are already beginning to see a shift in the way economy and society works, and the countless ways in which sector organisation have shifted online or adapted their in-person offers. However, the consequences of the suddenness of this shift are yet to fully play out.

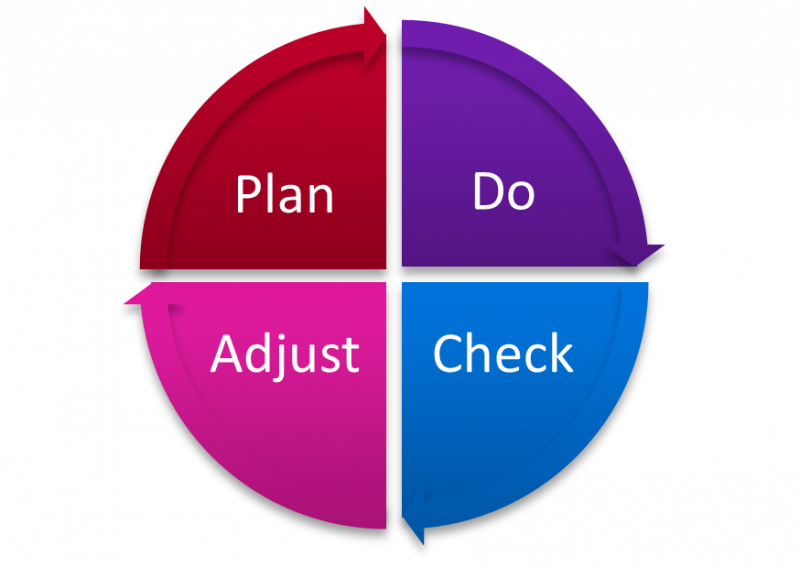

We can learn from Netflix, which makes nearly every product and business decision based on member behaviour observed in tests. It’s important to have a framework to assess what’s working; the Plan-Do-Check-Adjust approach is helpful in the current changing environment.

‘Plan’ means being clear about what you want to change or test. Museums, for example, might want to consider pricing by time slot. ‘Do’ means testing the change, either through action research or with a small study. ‘Check’ means reviewing the impact of the change, analysing the results, and drawing out the implications and ‘adjust’ involves deciding what to change. This will help you assess where you are under-performing.

Ultimately, the way we respond to any situation involves a delicate balancing act. Making the right decisions depends on recognising there is no set path to success, but using the information, guiding principles, and planning you’ve got to diagnose the situation and identify opportunities. In doing so cultural organisations can not only survive but thrive in an age of radical uncertainty, maximising income, increasing reach and maintaining accessibility.

To give King and Kay the last word: “Humans thrive in conditions of radical uncertainty when creative individuals can draw on collective intelligence, hone their ideas in communication with others, and operate in an environment which permits a stable reference narrative.”

David Reece is deputy CEO of Baker Richards.

![]() @davidnreece | @BakerRichards

@davidnreece | @BakerRichards

This article, sponsored and contributed by Baker Richards, is part of a series sharing insights into how organisations in the arts and cultural sector can achieve their commercial potential.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.