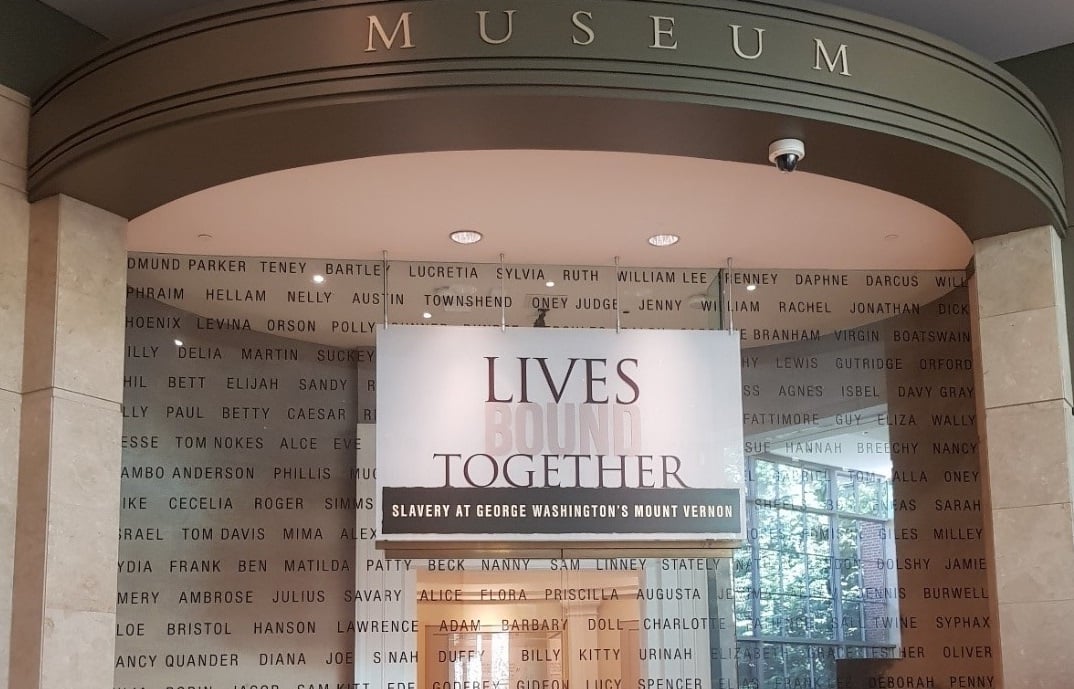

Entrance to ‘Lives Bound Together’ exhibition at Mount Vernon, Virginia, the home of first US president George Washington and family.

Photo: Tom Freshwater

How can heritage respond to a changing world?

Climate change, activism, funding constraints, policy priorities… How can museums and heritage organisations adjust their presentation, programming, collections and business models in response to the challenging world around them? Being adaptable is the only way forward, says Tom Freshwater.

At a time of political turmoil when budgets are hard to plan under great economic uncertainty, how can leaders adapt to a changing environment while continuing to deliver the mission and strategic objectives of their organisations and sustain their operation into the future?

At the National Trust I work with ‘inclusive histories’, bringing to the fore hidden and marginalised stories. In 2019 I went searching for evidence of enslaved people at Mount Vernon, the home of America’s first president, and found the ground-breaking ‘Lives Bound Together’ exhibition. In 1799 there were 317 slaves working for five Washington family members. How is this presented now, having been a heritage site since 1858?

A heritage organisation can suddenly find itself in the middle of a polarised debate with little preparation, resource or capacity to respond

Across 4,400 square feet, the historic collections of Mount Vernon are used to explore the lives of enslaved people. Individual biographies and timelines are created, and links made with living descendants to give acknowledgement and weight to this lived experience in the public historical record. It feels ethical, timely and in tune with our times – and leads what visitors experience at Mount Vernon.

Through my Clore Fellowship, I considered what lessons can be learned by well-established heritage and museum organisations in the UK who need to adapt the presentation, programming and interpretation of places, history and collections to better reflect the challenging world around them in the 21st century.

The need to respond

Beyond the formal political arena are ongoing challenges that all organisations must respond to. The climate change crisis has implications far beyond heritage. Sensitive and fragile historic landscapes, buildings and collections are having to cope with volatile climactic conditions. Protest movements for change, such as Extinction Rebellion, are inspiring declarations of solidarity and support from the cultural sector.

Social movements seeking better representation for marginalised communities are calling on heritage organisations to act. The 50th anniversary of the 1967 Sexual Offences Act in 2017 saw a groundswell of work in museums and heritage bodies to reflect LGBTQ stories and heritage. The #MeToo movement has shone a spotlight on the historic under-representation of works by artists who are women in museum collections, as well as examining relationships, partnerships and behaviours between artists, models and the ways source materials are presented and interpreted.

Increasing awareness and activism over historical injustices relating to colonial and oppressive historic actions such as slavery are requiring heritage bodies to respond. The #RhodesMustFall movement and the #MuseumDetox network have developed powerful ways to interrogate elite institutions and hold them to account for histories that may have been marginalised or erased as uncomfortable or troublesome. Our frameworks for decision making have to meet all these challenges.

The challenges of change

Research has shown that in times of challenge and austerity, large parts of the population reach out to connect with the familiar and the certain. At the same time other parts of the audience base want to see greater, faster change1. A heritage organisation can suddenly find itself in the middle of a polarised debate with little preparation, resource or capacity to respond, and feeling that whatever action it takes (including none) will lead to some harm to the organisation and its future activities.

These changing factors in society can lead to organisations being led by those with different values at senior and governance levels to those working in or being served by the organisation – for example, recent issues where artists have created work criticising the arms trade links of Board members at the Whitney in New York or Trustee resignations over the sources of sponsorship.

There may also be legal constraints relating to the way an organisation is constituted, as can be seen with the British Museum’s de-accession policy which has a strong presumption of retaining its objects regardless of campaigns calling for cultural material to be returned to origin countries.

The adaptive organisation

So given the scale of the challenges, what are the keys to successful adaptation?

• Stick to your mission

• Bring people with you

• Share power where you can

• Test and change the experiences you create

• Work with empathy and compassion

• Embrace complexity

• Influence the world around you

• Multi-channel programming

• Difficult means dynamic, not dull

It’s a list that has implications for the organisation and its visitors alike, namely:

Porosity – An organisation that is open to new thinking, new people and new ways to deliver its mission will have a better interchange with the society that it serves. It will be better informed about what people need from it, and how those needs can be met. More opportunities will emerge through these conversations, and more advocates and supporters for the organisation will be created.

Programming – For a heritage organisation the programme is best thought of as the full menu offered to visitors or beneficiaries. Just as food menus vary according to circumstance, a heritage or cultural organisation needs to do the same. It can be a place of reassurance to those that need it, for others a place of experimentation and daring, a testing ground for new ideas. Hypotheses grown through programmatic testing can become established, then adopted into core business once effectiveness has been proved.

Impact – An adaptable organisation is an impactful one, especially when it clearly articulates that its power derives from the relationships it has grown and nurtured. Such power can be the power to convene, or comment, or foreground, or balance. It doesn’t necessarily mean being the strongest or the biggest.

Adaptive organisations will reap benefits that will enable them to continue delivering their mission and strategic objectives well into the future, whatever the challenges and uncertainties.

Tom Freshwater is Head of Public Programmes at the National Trust in England, Wales and Northern Ireland, Europe’s largest conservation organisation. A 2018/19 National Trust Clore Fellow, Tom is part of the 15th cohort of Clore Leadership Fellows.

Clore Leadership

Clore Leadership was launched in 2003 by the Clore Duffield Foundation, to support and provide the professional development required to sustain the UK’s great cultural institutions, and international reputation for artistic excellence and innovation.

In the sixteen years since, the programme has succeeded in creating a sought-after cadre of creative and cultural leaders, and inspired investment in leadership on the part of governments, agencies, foundations and charities both nationally and internationally. It was and remains an exemplary intervention in our sector – Clore Leaders, some 2,220 alumni, are thriving and the investment in them is reaping significant rewards.

Our vision is for a society enriched by arts, culture and creativity, and Clore Leadership’s role is to cultivate excellence and innovation in the leadership of culture to help us get there.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.