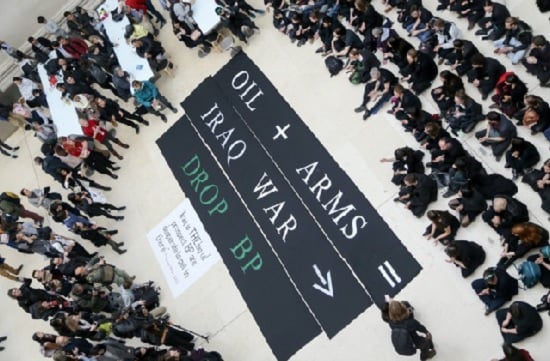

A protest against BP sponsorship at the British Museum

Photo: Diana More

Defending BP sponsorship: is it “for the public good”?

Chris Garrard dissects the public comments made by cultural leaders on the issue of ethical sponsorship.

Last month, the Director of the Science Museum, Ian Blatchford, made an extraordinary statement: “Even if the Science Museum were lavishly publicly funded, I would still want to have sponsorship from the oil companies.”

His comment drew a mixture of condemnation and bewilderment, as it followed weeks of mounting opposition to BP’s sponsorship of cultural institutions, from the 78 leading artists who demanded the National Portrait Gallery drop BP to the resignation of a British Museum trustee over the same issue. The directors of other oil-sponsored institutions have publicly adopted a more ambivalent stance, but is their approach to ethics actually any different? As concerns about climate change increase and scrutiny of sponsorship deals intensifies, are any of them doing what’s required to maintain the public’s trust?

‘Debate’ as a delay tactic

When Mark Rylance resigned as an Associate Artist of the Royal Shakespeare Company over its partnership with BP, the company’s Artistic Director Greg Doran and Executive Director Catherine Mallyon said they recognised “the importance of a robust and engaged debate” on sponsorship decisions given the acknowledged threat of climate change. This appeared to be a promising step forward, but the promise of debate should not be used as a smokescreen for delay and denial. BP claims to “welcome discussion, debate, even peaceful protest” on combating climate change and yet, the company keeps 97% of its business in fossil fuels. If we accept that art has the ability to challenge and change our thinking, then any genuine debate about how we fund the arts should include the genuine possibility of a change in approach.

Some directors though have remained resistant to substantive debate about whether, as the Museums Association’s Code of Ethics puts it, a sponsor’s ethical values are “consistent” with those of their institution. Instead, they evade scrutiny by deflecting attention to visitor numbers or other measures of impact that sponsorship – or the loss of it – creates. In the British Museum’s case, Director Hartwig Fischer has repeated the claim that without BP’s money some temporary exhibitions would “simply not be possible” . While funding pressures are real, the small proportion of the British Museum’s income that is provided by BP would not be unattainable elsewhere, potentially from sponsors or donors that don’t create such clear ethical conflicts.

Any genuine debate about how we fund the arts should include the genuine possibility of a change in approach

When Director of the National Portrait Gallery, Nicholas Cullinan, came under pressure to defend the institution’s BP sponsorship deal, he claimed the gallery was committed to acting “in good faith and for the public good”. But determining what is genuinely for the public good requires an accurate assessment of the transactional nature of the gallery’s relationship with BP beyond highlighting the standalone statistic that 275,000 people saw artworks funded by the BP Portrait Award last year. These metrics are not unimportant, but they offer only a partial picture, not an ethically sound defence of the sponsorship deal. They must be assessed alongside BP’s seat on the Portrait Award’s judging panel, as well as the legitimacy the company gains from its association with the gallery which, by extension, legitimates its plan to “invest in more oil and gas”. According to the Fundraising Regulator, this kind of corporate partnership must be backed by “a process of due diligence proportionate to the scale of the relationship”. Given the extensive branding benefits BP gains from the sponsorship, this should have been a thorough process. But it is not clear whether the gallery carried one out at all: when asked in 2016, it could not find any record of a due diligence process when BP was first accepted as the Portrait Award’s sponsor in 1990. If this hasn’t happened since, can Cullinan really claim to be acting in good faith?

Finding a ‘balance’

Sound ethical judgment does rely upon a degree of objectivity and a willingness to think critically, which is why this clear due diligence process is essential. Following Ahdaf Soueif’s resignation from the British Museum’s Board, in part over its continued BP sponsorship deal, its Chairman, Sir Richard Lambert, defended BP’s record as a major British employer that was committed to the Paris Agreement – it has actually committed to disclosing how its strategy is aligned with the accord. Rather than fully engage with the legitimate concerns of a former trustee, Lambert suggested Soueif’s resignation had made little difference: “We obviously discussed afterwards as a board what our position on sponsorship should be and we have not changed our mind.” This underscores the importance of having an ethics committee that works through a transparent process, ensuring that decisions about sponsorship are defensible and based on evidence without potentially compromised voices holding sway.

These explicit defences of oil company sponsorship from Lambert and Ian Blatchford have been a striking departure from the more equivocal tone still adopted by others. When the Chief Executive of the Royal Opera House, Alex Beard, came under pressure to defend his institution’s BP deal, he said: “whilst we prioritise meeting our environmental obligations, we balance this with BP’s ongoing support providing free access to our art forms”. Too often this concept of ‘balance’ – which dominates a lot of debate about ethical sponsorship – is flexibly applied with only those who, in Beard’s words, have “benefited during 30 years of BP sponsorship” are factored in and those impacted by BP’s business over the same period go unacknowledged. If, as Beard claims, he shares “the goals and concerns of those campaigning for a sustainable future”, he must be prepared to be accountable to them too.

With a growing awareness that climate change is a social justice issue, an approach to ethical sponsorship that hinges on this notion of balance may not always be appropriate – and it certainly has its limits. The issues we face today require a greater discussion of rights, responsibilities and fundamental values, all things which are core to the cultural sector but difficult to measure. The practical pressures of funding cuts can’t be dismissed but, in a time of climate emergency, ethical judgments about sponsors need to go beyond metrics and money.

Chris Garrard is the Co-Director of Culture Unstained, a research and campaigning body opposed to oil sponsorship in art.

www.cultureunstained.org

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.