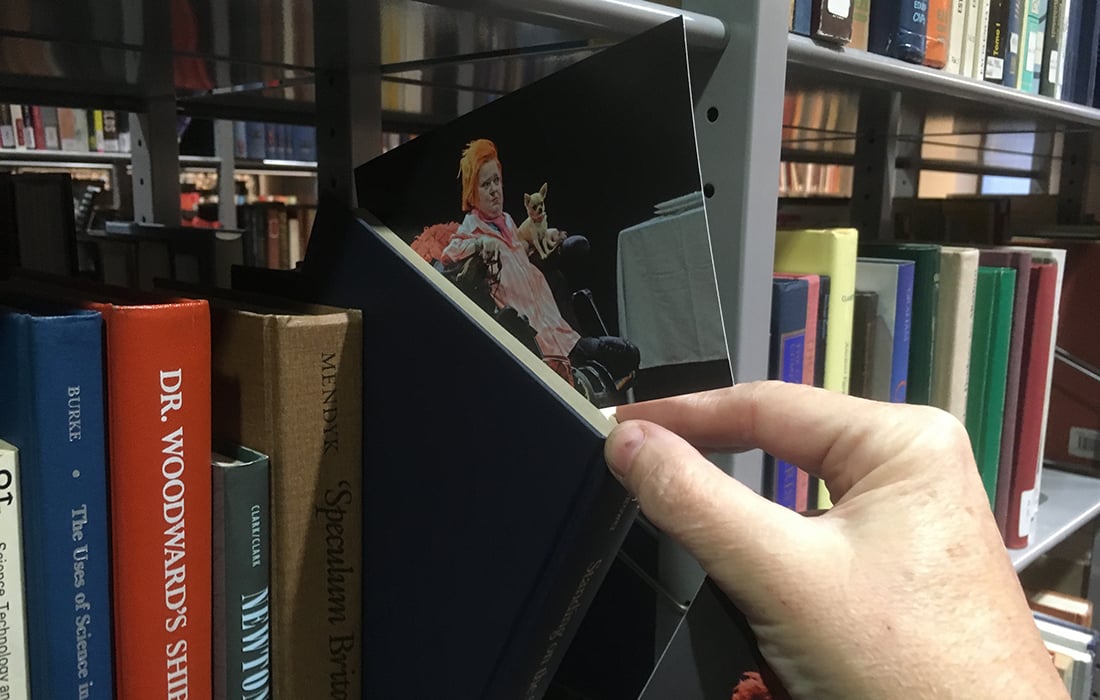

Postcards of artist and activist Katherine Araniello have been mysteriously appearing in books on library shelves across London

Can cultural organisations ever be radical?

Once-ridiculed activists are increasingly setting the agenda, but can radical practices co-exist with organisational forms adopted from mainstream culture? Lois Keidan examines the evidence.

What can activism look like these days? It can look like Asia Art Activism’s ‘Unapologetic Coughing’ event in London last month – a performance by AAA artist in residence Youngsook Choi alongside a discussion about the racism surrounding the spread of the coronavirus and the “repetitive narrative of using pandemic hysteria as a justification of violence towards socio-cultural minorities”.

Or it can look like the postcards of the artist and activist Katherine Araniello that have been mysteriously appearing inside books on library shelves across London since December last year. Katherine’s politically fearless and audaciously funny film, performance, and digital art about disability and the aesthetics of the body undermined the ways in which ‘different’ bodies are ostracised within society and misrepresented within culture. Following Katherine’s death in February 2019, an anonymous artist-activist has inserted her, and all she represents, into the pages of ‘official’ histories – especially those in medical libraries: a literal and conceptual intervention into the narratives and politics of ageing, sick and disabled bodies. Narratives and politics that, as the disabled artist Martin O’Brien recently said, are “being thrust into the spotlight in a devastating way” with the coronavirus pandemic.

Artist-activists are not making art that is about politics, but art that is politics

Or it can look like Liberate Tate, a network whose artistic practice is to conceive disruptive, ‘performed’ actions within museums and who made art itself a form of resistance and protest. Liberate Tate was formed in 2010 by artists who wanted to liberate Tate from its sponsorship by BP, a relationship that they believed gave a corporation directly responsible for contributing to the climate catastrophe a ‘social licence to operate’ and one that damaged Tate’s reputation and civic responsibilities. For years Liberate Tate were mocked and dismissed by many of our cultural grandees, whilst big institutions like Southbank Centre, the National Gallery and the Royal Shakespeare Company continued to greenwash the dubious business practices of oil companies through sponsorship deals.

Not any more. As an increasingly wider (and younger) public expects cultural institutions to look to their own operations and values, those institutions are dropping dodgy sponsors like stones. The activist tactics of Liberate Tate are now recognised as being instrumental and prescient, and those grandees as being on the wrong side of history.

Responding to the times

Live Art is a way of thinking about what art is, what it can do, and where and how it can be experienced. It’s art that seeks to be alert and responsive to its sites, its audiences, and its times. Live Art and activism have a long and symbiotic history. Like Liberate Tate, many artists working in Live Art see their practice as a form of activism, and many activists use performance methodologies and strategies of creative resistance as key components in their toolkits: look at the way Extinction Rebellion ‘stage’ civic interventions and ‘choreograph’ people’s movements.

In 2004 the artist-activist John Jordan led one of the Live Art Development Agency’s (LADA) annual artist-led ‘DIY’ professional development programmes. John’s project, ‘Response-Ability’, was a weekend retreat for 20 participants that set out to ‘build bridges’ between art and activism by politicising artists and aestheticising activists. The weekend generated all kinds of new practices and spawned the anti-capitalist collectives The Laboratory of insurrectionary imagination (Labofii) and The Clandestine Insurgent Rebel Clown Army (CIRCA).

John Jordan, Liberate Tate and other activist-artists/artist-activists are not making art that is about politics, but art that is politics. This kind of thinking informs LADA’s mission and values and the practices and practitioners we support through our programmes, publications, and resources. These include countless DIY projects like John Jordan’s that have explored, or even birthed, new forms of activism and new strategies of creative resistance.

Marginalised artists

Live Art has become a potent and productive space for artists working with issues of environmental and social justice. Just as significantly, Live Art has offered a context and a form of agency for marginalised and underrepresented artists who don’t ‘fit’ within cultural and social norms. These may be artists of colour or queer, women, disabled, trans, displaced, or working-class artists. As a practice that does things differently, Live Art has become a useful space for those who need things to be done differently. It is a space of and for difference – and one that can make a difference.

But should art that operates and thinks ‘differently’ also be created, produced and funded differently? And if so, can the cultural institutions that support contemporary artists and practices ever be radical themselves? And if they can, what might that look like? That is the question that LADA is asking over the next twelve months as we continue our current research project ‘Managing the Radical’ (2019-2021). This involves rethinking what forms of management and methodologies of production might be more appropriate and effective for radical new forms of artistic practice.

The first phase of this project took place across LADA’s 20th anniversary year in 2019 in collaboration with the Managing the Radical Action Group (Amitabh Rai and Nicholas Ridout of Queen Mary University of London, Gini Simpson of The Sick of the Fringe, and producers Orlagh Woods and Cecilia Wee). Through a series of gatherings we invited guests and interested publics to bring their own histories and political and economic priorities to the table. These events focused on Radical Care, Experiments in Self-Organising, and Power, Money, and Counter-Power.

Take the money and run?

There is a global crisis of care. In all aspects of our lives we are now supposed to take care of ourselves – sometimes at the expense of taking care of others – and to privatise or outsource care. The consequences of this pose many challenges for artists and arts workers, particularly where artists are dealing with the complex issues and highly politicised territories around identity politics. The ‘Radical Care’ gathering suggested that there are possible alternatives grounded in collective action and solidarity. We explored how self-organisation might invent alternatives in responding to this crisis. Could we learn from the past and from each other in order to care better for one another…or even just to care?

How we organise what we do determines what we can do. A truly radical practice is unlikely to emerge from a conservative, rigid or hierarchical organisational structure. The ‘Experiments in Self-Organising’ gathering considered what forms of organisation might best support and sustain experimental practice and asked whether radical practices can co-exist with organisational forms adopted from mainstream culture or business. How might we learn from frameworks found in other radical practices, such as those within organising, activism and diverse communities? Or do we have to devise our own?

Reflecting on the achievements of activists like Liberate Tate, the ‘Power, Money, and Counter-Power’ gathering invited anyone engaged with these issues to share ideas about how we might build for future struggles to free art and artists from their dependency on the proceeds of toxic capitalism. The event asked what a politically and environmentally responsible approach to money in the arts might look like. The power of capital to ‘cover’ its tracks has increased with the financialisation of everyday life, where complex schemes hide networks of money laundering the world over. In parallel, the power of arts organisations to rehabilitate the agents of disaster capitalism through little and big acts of ‘artwashing’ has also increased. In these globalised contexts of power and corruption, we considered who is able today to ‘take the money and run’.

The findings from these gatherings and the wider research phase of ‘Managing the Radical’ will also be LADA’s focus in 2020 as we undertake an extended process of organisational reflection, reimagine our own ways of working and consider what our roles and responsibilities should be to art, artists, and the wider world for the next 20 years. Watch this space.

Lois Keidan is Director of the Live Art Development Agency.

![]() thisisliveart.co.uk

thisisliveart.co.uk

![]() @thisisliveart

@thisisliveart

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.