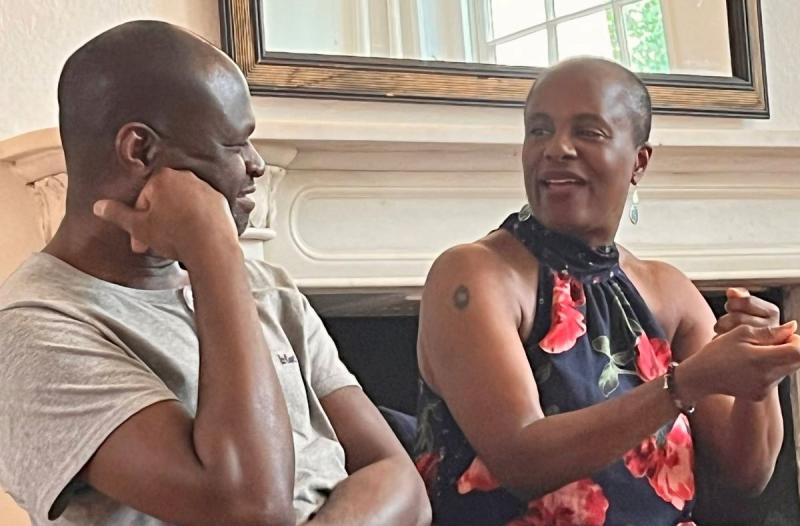

Students on the Black British Theatre program visit Talawa

Photo: Kimberly K. Harding

Lessons from Black British theatre

Kimberly Harding’s desire to study Black British theatre was born decades ago. This summer she travelled to London to make it happen.

I believe in divine guidance. Everything that happens in life unfolds as it should. This is true of my journey to the Black British Theatre program at the British American Drama Academy (BADA) in London this summer. The journey was long, but well worth the wait.

My desire to travel to London to study the history and culture of Blacks in British theatre began roughly two decades earlier. In the 1990s, I read Deep are the Roots: Memoirs of a Black Expatriate by Gordon Heath.

Heath was an American actor whose career spanned work on stages in New York, London and Paris. His memoir recounts his leading role in the 1945 Broadway production of Deep are the Roots by Arnaud d'Usseau and James Gow and its subsequent six-month run in the West End.

My fascination with his story centred around the notion that Black American actors played a significant role in the development of Black British theatre. According to Heath, some helped to train actors – particularly of African and Caribbean heritage – while others helped form companies and ignite social activism.

I hungered to learn more about the development of Black British theatre. The thought lingered.

The fight for equity

As an instructor of a Contemporary Black Theatre course, which primarily focuses on African American theatre history, I have observed a large number of Black writers impart the impact of race and racism on African Americans in their plays.

As the recent resounding call for change erupts and disrupts long-held systemic racial practices in American theatre, it isn’t a new voice. This cry has been heralded and mostly ignored since the inception of the African Grove Theatre in New York in 1821.

From the activism of the New Negro movement during the Harlem Renaissance and the Civil Rights and Black Arts movements of the 1950s and 60s, Black arts administrators and practitioners have continuously fought for institutional equity.

This caused me to wonder: Has this struggle for justice been the same for Black creatives in London? For all people of colour worldwide? The thought lingered.

Pandemic postponement

In December 2021, a colleague forwarded an email from BADA announcing a new Black British Theatre program. Its website description aligned with my interest.

Excited, I immediately applied and was accepted. However, the pandemic had immobilised the world. As the start of the program in summer 2022 approached, BADA made the difficult decision to postpone launch until summer 2023.

Course curator Oladipo Agboluaje with playwright Winsome Pinnock at BADA. Photo: Kimberly K. Harding

Course curator Oladipo Agboluaje with playwright Winsome Pinnock at BADA. Photo: Kimberly K. Harding

Surprisingly, the course curator, Oladipo Agboluaje, and Eunice Roberts, BADA’s Dean, pulled together a delightful precursory event. Applicants were invited to experience a video recording of Winsome Pinnock’s Red Lights and Blue Rockets, followed by a moderated discussion and Q&A with the playwright.

Maybe the plays of Black British writers do bear the brunt of racial representation and of remembering. The thought lingered.

The program did not disappoint

The day BADA finally opened its doors to the first cohort of the Black British Theatre program, I felt closer to my answers. I was the elder of fifteen Black participants, hailing from three different countries and various walks of life.

We met at Gloucester Gate in London eager to gain a deeper understanding of and a greater appreciation for the contribution of Black British practitioners and their histories, traditions and culture. The program did not disappoint.

Each week, Monday through Friday, we studied with celebrated tutors. Monday mornings, Jamaican-born British actor and director, Anton Phillips sprinkled dates and facts into engaging stories and personal accounts of the progress and development of Black theatre in his lectures on Development and Context of Black Theatre in Britain.

Each Tuesday, award-winning African performance artist, Patrice Naiambana’s thunderous voice and spirited enthusiasm energised us in his Diasporic Performance in British Theatre course.

Playwright and academic, Agboluaje’s inquiry approach to play analysis challenged us every Wednesday and Thursday during African-British Narratives and The Dual Heritage Experience courses, while Dr Natasha Bonnelame, author, educator and an associate of the National Theatre’s Black Plays Archive, taught the historical significance of The Female Narrative.

Generous sharing of experience

From them, I gained knowledge about a history often omitted from British stage history. I learned that companies like Black Theatre Cooperative, Temba and Talawa Theatre entertained Black audiences, while writers like Mustapha Matura, Bola Agbaje and Debi Tucker Green, detailed the joy and pain of living in London.

White companies including the Royal Court,and the Kiln theatre (formerly the Tricycle) were safe inclusive spaces for Black creatives. But these were exceptions.

In addition to lectures, our busy schedules were filled with afternoon workshops, live theatre and cultural excursions. Acclaimed Black playwrights, including Pinnock and Roy Williams, generously shared their lives and careers, as well as challenges and triumphs in the London theatre scene.

We witnessed performances, including Clarisse Makundul’s Under the Kunde Tree at Southwark Playhouse, Lenny Henry’s August in London at the Bush Theatre, and Dave Harris’s Tambo and Bones at the Theatre Royal in Stratford East, among others.

We visited places of Black diasporic culture and heritage such as the Africa Centre, dined and shopped at Brixton market, and were guided on a tour of the London, Sugar and Slavery exhibition at the Museum of London Docklands by actor and broadcaster, Burt Ceasar. All experiences a book could only recount.

Some things are worth waiting for

No matter how many books I might have read about Black British theatre, reading could never have given me the experience of standing between the Old Vic and the National Studio chatting with playwright Mojasola Adebayo, and with Femi Elufowoju Jr, co-founder of Tiata Fahoddzi, who just happened to be in the area.

Students on BADA's Black British Theatre program are greeted by the Young Vic's Artistic Director, Kwame Kwei-Armah. Photo: Kimberly K. Harding

Students on BADA's Black British Theatre program are greeted by the Young Vic's Artistic Director, Kwame Kwei-Armah. Photo: Kimberly K. Harding

It could never have offered the experience of watching Kwame Kwei-Armah and the cast of Beneatha’s Place in rehearsal at the Young Vic, invited by the playwright and Artistic Director himself, who shared his creative process with us.

I would have never met Michael Buffong, Artistic Director of Talawa Theatre in East Croydon, or toured the theatre space, or experienced the company’s production of Recognition. Some things are worth waiting for.

Course was eye opening

Through it all, my questions were answered. Like Black theatre in America, the subject of Black British writers has been largely repressed. Black plays largely reveal the existence of classicism and racism towards Britain’s African and Caribbean immigrant population. But things are changing.

Driven by an industry-wide movement to eradicate a culture of white supremacy, as in America, British theatre is improving representation and bias. Lynette Linton’s 2019 appointment as Artistic Director of the Bush Theatre is an example. Playwright Natasha Gordon’s 2018 moniker as the first Black British female playwright to have a play produced in the West End is another. These steps are small, but the reverberations are widely felt.

My time at BADA was eye opening. Black theatre has a rich history in Britain. It should be studied in theatre curricula across the nation. As a life-long learner, I think all students would benefit from such a course, no matter their race or ethnicity. A deeper understanding of the subject encourages social equity for British artists of the African diaspora.

The course demonstrates the growth of British theatre from the contributions of Black creatives. It celebrates the Black writers, directors, performers, artistic directors, activists and plays of the past and present that will continuously influence the future of British theatre.

Kimberly K. Harding is Associate Professor of Theatre at Florida A&M University.

![]() www.cssah.famu.edu/ | www.bada.org.uk/

www.cssah.famu.edu/ | www.bada.org.uk/

![]() @FAMU_CSSAH | @BADAONLINE

@FAMU_CSSAH | @BADAONLINE

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.