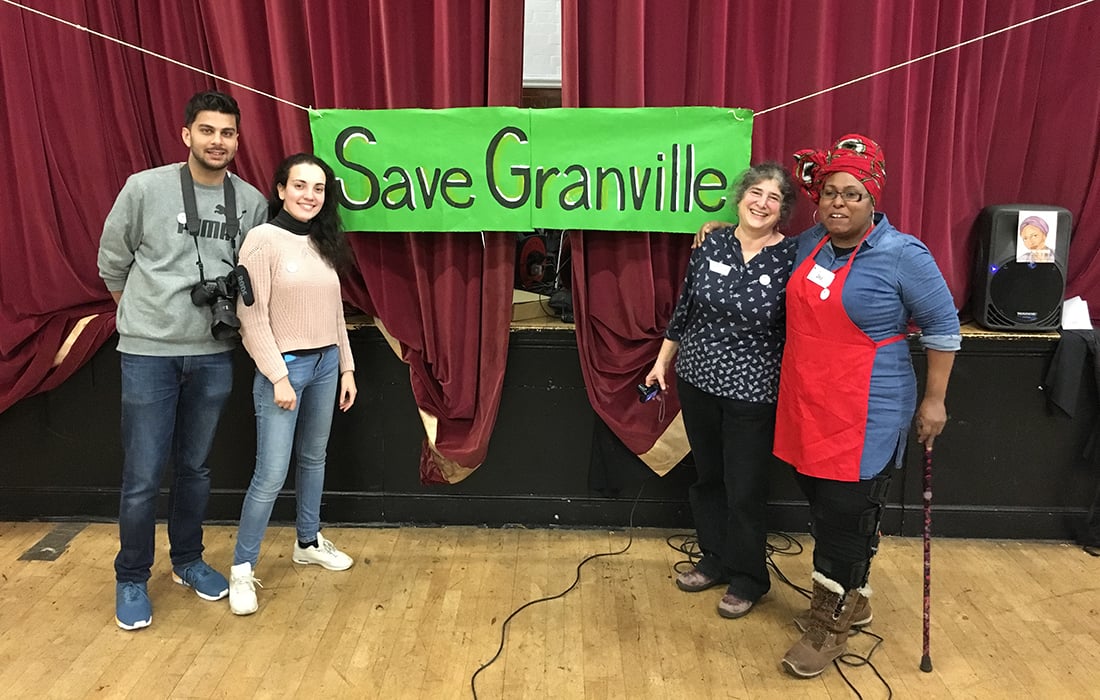

Granville Community Kitchen: campaigning to ‘Save Granville’

No community spaces? No community arts

Community arts organisations are at the heart of the response to the Covid-19 crisis, but their spaces are threatened by arguments that focus on the economic value of the arts. It’s time we started measuring social value, says Zain Dada.

Last autumn the community of South Kilburn in the London Borough of Brent packed out the Granville Centre for an evening of poetry and film organised by the Granville Community Kitchen. It included the launch screening of Granville, For Us, By Us, a new documentary by local film-maker Dhelia Snoussi, which was created as part of an intense local campaign fighting for the survival of two 100-year-old community spaces – the Granville and Carlton Centres

The Granville Centre was built in the 1880s, originally as a Presbyterian hall before serving the South Kilburn community as a wedding hall, music venue, event space and much, much more. Next door, the Carlton Centre, currently occupied by another local group, Rumi’s Cave, have hosted regular spoken word nights, talks and film screenings in the area for several years.

Despite both spaces being key, historic community hubs, they are set to be replaced by a new housing and commercial development. And the irony is, they could both disappear in the same year as Brent’s Borough of Culture.

Community arts need homes

South Kilburn was recently described by the Evening Standard as the “rotten core of an apple”, so the City Hall’s Borough of Culture Award, awarded to Brent in 2018, heralded a much needed cash injection of £1.35m funding to support ‘culture for everyone’ in the area. Based at the Granville Centre, the Brent 2020 team have worked tirelessly to deliver a range of diverse programming, which began in January 2020 before the Covid-19 global pandemic caused cancellations. Inevitably, as with other venues and public programming, some of this will shift to 2021.

Whilst the programme for Brent 2020 is supporting artists and organisations in Brent, the futures of both the Granville and the Carlton Centre is less clear. Both spaces are locked in a battle with Brent Council who are set to reduce community space significantly to accommodate 18 flats and an enterprise hub. This new scheme doubles down on a prior attempt by the Council in 2016 to demolish the Granville Centre and replace it with unaffordable housing in 2016, which faced widespread resistance from local activists and author (and ambassador for Brent 2020) Zadie Smith.

So the question is, how successful can an effort to boost community arts across London be if the public spaces which have hosted cultural activity for generations disappear?

Mapping first

The story of Granville and many other community centres like it across the country, is a story of space and survival. As local authorities across the UK should be looking at long-term, sustainable solutions in a post-Brexit, post-Covid-19 world, my research into the future of community arts organisations in the United States – where the community arts sector has many parallels with the UK – shows what those solutions could be.

A valuable insight comes from, Mapping Oakland, a research project which examined community arts organisations in Oakland, California, ranging from informal arts hubs and art spaces to collectives. It was based on interviews with locals and focused on organisations with annual budgets of $250K or less. Mapping local arts and culture activity requires a thorough methodology and an understanding of the race and class dynamics which define who has the social capital and resource to sustain or grow their organisations. Crucially, it provides an insight into which organisations are essential local hubs, what barriers might exist and where opportunities to up-skill might be. Without a process of mapping, many local organisations are rendered invisible and struggle with the burden of maintaining themselves through the unpaid labour of local volunteers.

An actionable approach to giving practical support to community arts organisations needs to follow. In San Francisco, the Community Arts Stabilisation Trust (CAST) works toward addressing astronomical market rates for space by stabilising or freezing rent for long-serving, local community arts organisations. CAST’s modus operandi also involves purchasing leases using tax credits for community arts organisations in the area, as well as boosting the financial acumen of those organisations.

In February 2019, City Hall initiated the Creative Land Trust which models itself on CAST and is a step in the right direction. However, the Creative Land Trust prioritises ‘affordable workspace’ and ‘artist studios.’ That approach needs extending to include historic community centres, youth centres and informal hubs which are often the glue for socially divided communities.

Social value

Attitudes toward the value of public spaces need to shift. Language around ‘economic growth’ and the arts is rife. It can be a politically expedient response to argue for more funding from central government. However, the economic argument can also provide justification for local councils to propose that public and cultural spaces should be demolished under the guise of being ‘under-used.’ What we require is a measurement for ‘social value’ which enshrines an evaluation of historic presence and the social need for public spaces which incubate and grow so many essential community arts endeavours we value today.

As for the Granville Community Kitchen, in the midst of our unprecedented global crisis, volunteers have been busy prepping aid packages to vulnerable people in Brent. Like many other community organisations across the country, frontline welfare work and arts and culture are at the heart of their existence.

Zain Dada is Writer, Cultural Producer and Programme Manager for Maslaha

Www.ZainDada.co.uk

@ZainDada92

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.