Attracting audiences other artforms cannot reach

How do outdoor arts have the potential to reach audiences other artforms can’t, and how can we best support the sector, asks Penny Mills.

The Audience Agency’s past six years of sector-partnered research paints a positive picture of the inspiring and creative outdoor arts that take place in our cities, towns, villages, hillsides and beaches across the country. Audiences are wide-ranging, youthful, diverse, aligned with the English population and representative of a public not frequently engaged in the arts.

Partnerships between venues and festivals provide opportunities for a year-round presence, while strategic relationships with community hubs develop year on year

These audiences are more youthful than those of other artforms, with 43% of attendees aged 25 to 44. They are also more ethnically diverse, particularly at the younger end of the spectrum, where 44% of outdoor arts audiences aged between 16 and 24 are non-white.

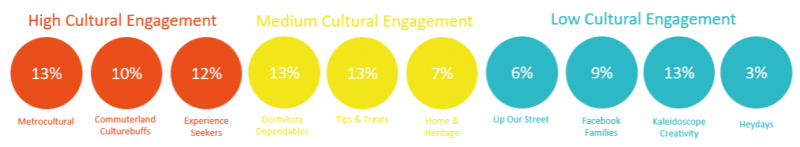

Audiences for outdoor arts are unusually evenly spread across engagement levels and in line with the English population at large. 34% of households are low cultural engagers, yet 31% of surveyed outdoor arts attenders come from the lowest culturally engaged groups. This sits in stark contrast to indoor or ticketed arts, for which low engagers constituted just 17% of the 2017/18 audience.

The artform has a clear ability to connect with these people and bring them together. 82% of audiences come in groups, with 73% expressing social motivations for attending, a statistic that reflects particularly well on collaborative endeavours.

Community collaborations

Over the past few years the Without Walls Associate Touring Network, supported by the ACE Strategic Touring Fund, has helped its partners to develop more inventive and artistic ways of developing audiences in areas of little arts provision or low cultural engagement. Similarly, collaborations that support programming initiatives, such as Global Streets, have brought scale and spectacle, while Coasters has injected neglected seaside spaces with renewed vigour and vibrancy.

Mela are significant not only as a celebration of South Asian arts, but as flagship opportunities for a community to come together, regardless of ethnicity, while the carnival model has a lot to teach us about community activism. It’s unsurprising then that numerous Creative People and Places and Cultural Destinations projects have integrated outdoor arts into their programmes, and many Great Places projects look set to follow suit in the near future.

A growing body of case studies and expertise demonstrates how these artists, companies and festivals are reaching and engaging eclectic audiences through taster events in out-of-town communities, participative workshops, family activity areas and mass participation events. Partnerships between venues and festivals increasingly provide opportunities for a year-round presence, while strategic relationships with community hubs develop year on year and some artists are working closely with communities over the longer term.

Opening doors

And yet the door remains ajar, not fully open to attracting and inviting support and funding. So, what else can we do to increase the resilience of the sector? What else can we say to state its relevance more clearly? Most of all, how can we support it to realise its potential to transform individuals, communities and places?

This is where the passion of those working in the sector is crucial. It’s a passion that can transform the most familiar places into arenas of adventure and exploration, seek out heroes in a crowd, enhance a natural landscape by harnessing nature itself, or draw in disparate strangers standing on a street corner as they sigh, scream and gasp as one.

Further support requires efforts on two connected fronts:

- Identifying stories that will influence those we need to appeal to.

- Focusing on developing engagement practice, designed to realise the potential of outdoor arts.

First, we need to create an open dialogue with potential partners to understand what their objectives are. Although we should always talk to partners who are on our wavelength, or who can be brought around, it should not be the tail wagging the dog.

Second, we need to be talking in specifics and not generalities. Not ‘diversifying audiences’ but ‘reaching specific demographics’. Not ‘improving social integration’ but ‘bringing two communities together in dialogue’. Not ‘having an economic impact’ but ‘assessing the use of local suppliers, spend, dwell time, numbers of day visitors or overnight stays’.

Third, we need to ask why 67% of audiences are likely to be actively promoting attendance at the event to their friends and relatives. Does this represent an increase in their pride in a place? If so, whose pride, and what was the most significant change (small or large) that led to it?

Finally, we need to be collecting information in a robust and consistent way. Many potential partners need us to demonstrate what is already happening before they come on board, so it can be a long road.

Engagement and advocacy

Most importantly, though, whichever of outdoor arts’ amazing capabilities are most relevant in any given context, we need to be designing the way we work so that the ambitions for individuals or communities have a good chance of being achieved. We need to learn more about the alchemy that underpins those transformations – the who, the what and the how – and be sharing this across the sector.

The work of Creative People and Places continues to clarify this ‘who’-centred focus. The recent report by Sarah Boiling and Claire Thurman has tracked the ‘what’, mapping the approaches taken by CPPs, and our forthcoming work evaluating the London Borough of Culture aims to get to the heart of the ‘how’. Both initiatives share the key intention to ‘work with’ and not ‘do to’ the communities involved – and we know that takes time and energy.

Engagement practice is an artform in itself and we should be better at supporting a diversity of artists, presenters and producers to develop dialogue and skills in this area. Reflection needs to be embedded and no activity should pass without someone asking the question of the audiences and participants: “What difference has this made to you and why?” We should never assume.

Then we can advocate for the outdoor arts on a different level, to a wider range of partners, with the confidence of the evidence behind us. Then we can have lasting and transformative effects for the communities involved. And, most importantly, we can understand something more about how the transformation came about and how to advance the alchemy.

Penny Mills is Director of Consultancy at The Audience Agency.

www.theaudienceagency.org

If you are interested in receiving The Audience Agency’s Outdoor Arts sector report, sign up here.

This article, sponsored and contributed by The Audience Agency, is in a series sharing insights into the audiences for arts and culture.

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.