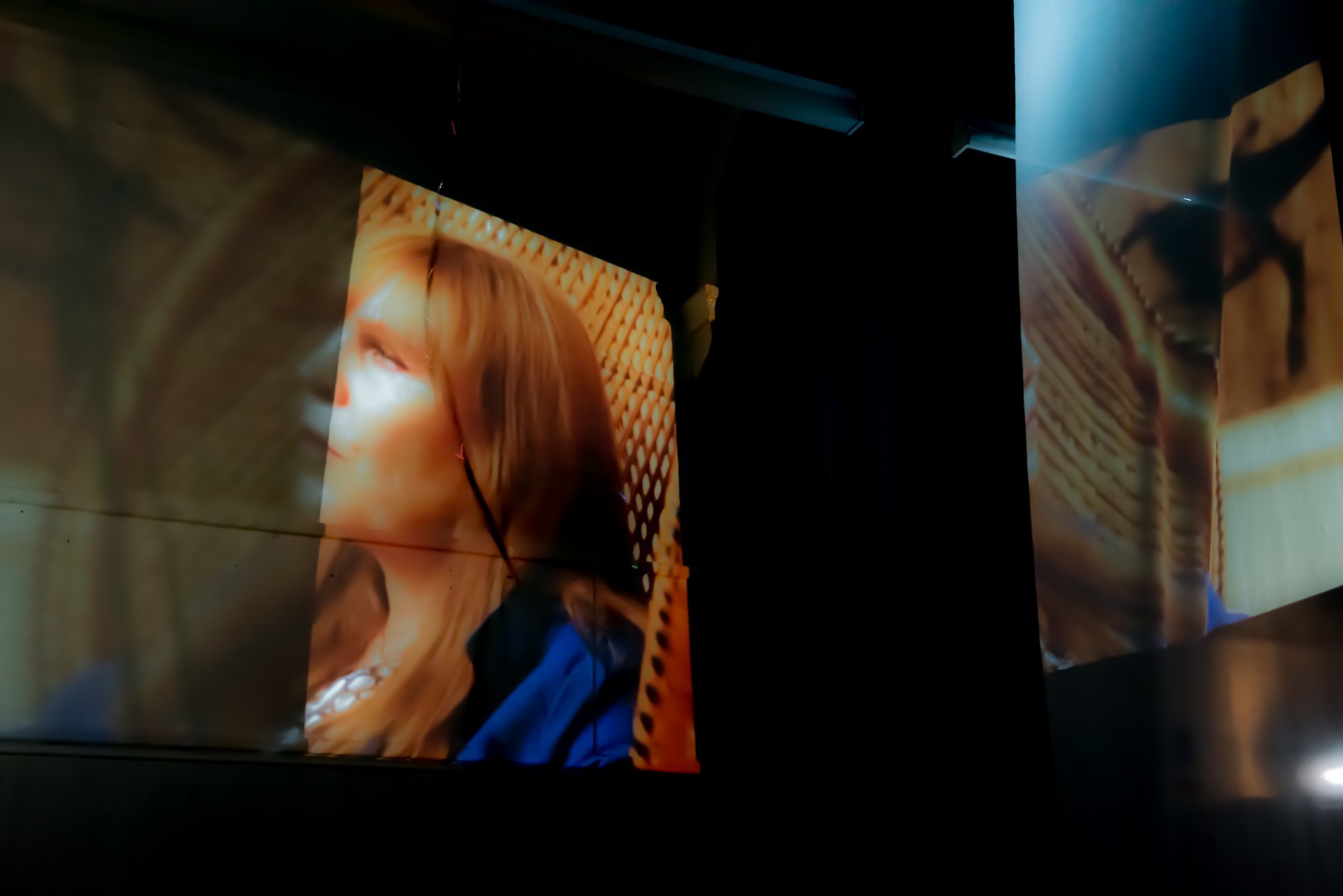

An installation at Proteus Theatre's CONTACT project

The commissioning game

Do commissions from funding bodies based on measurable outcomes really benefit arts organisations? Ross Harvie reflects on the issue.

While at Improbable Theatre’s January 2014 Devoted and Disgruntled event, I took the opportunity to try and determine what it means to measure outcomes in the arts. I have worked in the arts for nine years and in that time I have become very used to collating and measuring outcomes for funders: the number of people who attend performances, the number of people who took part in a workshop, the number and locations a performances ran in, the list goes on.

In recent years, as funders’ requirements for data have become more onerous, I have been required to collect audience data relating to geographical location, ethnicity, feedback, and even been required to provide photos to demonstrate that the project or performance had been delivered. These reports, particularly for local authority funding bodies, have become a standard, automatic part of the general evaluation process.

Commissions can restrict the natural direction and flow of projects, and this can lead to less positive, neutral or even negative outcomes

But does any of that measure outcomes? Arts Council England, trusts and foundations are very focused on outcomes. For core funding that derives from local authorities it is rare that I am asked to report on outcomes − what was achieved by taking theatre to a certain location or the impact that a certain show had on its audience.

I must admit that I am guilty of rarely considering what lasting impact our shows have on our audiences. Although they may be on our mailing list and receive regular contact from us, I do not think to ask about their views on our performances once the initial post-performance feedback has been gathered. Are they still thinking about a production two days, two weeks, or even two years later? With social projects, however, it is so much easier to stay in touch. For example, I was recently informed that four participants who attended our recent mental health project, CONTACT, have been able to return to the workplace or have found positions as volunteers within the local community. An important and positive outcome of the project. Suffice to say, it is an incredibly positive outcome when participants find themselves willing and able to leave their homes to access the project. For one in particular, an agoraphobia sufferer who had not felt able to leave their home in two months, the outcome is clearly quantifiable, and undeniably positive.

For me it comes down to how we measure happiness. But how do I ask a participant with depression how happy they are? Their answer will most likely be subjective, not only influenced by the project itself but also by a myriad of external factors. However, we do know that we will have contributed to their general health and wellbeing − in short, their happiness − through their engagement with and involvement in the activity.

So how can we generate such positive outcomes across all the arts, not just the social projects that we know tick big boxes?

I am keen to protect the arts that do not have a social impact. You know, the high-quality, big budget stuff that looks amazing and makes us smile. My protectiveness stems from a move in local authority funding from a grant-giving to a project-commissioning philosophy. Commissioning is about saving money in a world of ever-tightening public purse strings. But it is also about defining clearer outcomes for local authorities.

New Local Government Network’s (NLGN) new report, ‘The Road Not Taken: New Ways of Working for District Councils’, says “If districts are to be fit for the future then they must relentlessly focus on achieving the best outcome for people and place.” Our local authority is asking “What could the council be doing itself and with its partners to deliver a range of arts and cultural activities that are attractive and value for money for the borough?”

The commissioning game is tricky for artists. My research suggests that commissions can restrict the natural direction and flow of projects, and this can lead to less positive, neutral or even negative outcomes. I know that we need to develop and invest so that we are fully prepared for the future of commissioning. We need a long-term evaluation process, one which will form part of our future business plans, to measure the impact our work has on our audiences further down the line. This may prove to be impractical in some cases, but we want to invest in developing a longer, deeper relationship with our audiences, not just when we are touring.

We have recognised that we must develop a new way of communicating with our funders, particularly where (as is often the case in some regions) there is no longer an arts service with arts officers in place. Most importantly, we have to get the anecdotal evidence right, bearing in mind that the stories of real people may not be science but are very important if put across strongly. We might be less free to shape our projects once we have started, but we will know which outcomes we are working towards. After all, we know our stuff and we are best placed to measure our achievements. We must have the determination to stick to the targets, linking this back to our aims and ethos and, most importantly, our organisation’s vision. We can still make our work creative, fun and enriching and the staple part of using the arts as a catalyst for change.

The argument for arts funding may not be the best argument to have in the current climate; individual, local stories may carry more impact. We must not get caught up in the outputs debate. Quality must come before quantity. And, finally, we must make the most of all the external resources available to us and not lose sight of the fact that one hour a week with our participants may not be long enough for us to make a huge difference by ourselves. The limits of time and resources are always against us within the realms of our funding.

There is so much for audiences to engage in out there and we must get better at collectively measuring outcomes. By working together as an industry we are stronger. We should not ignore non-industry work such as in the amateur sector, but work with it to measure engagement in the arts. We must remember that the audience is the most important stakeholder in our work as initial funder of their respective local authorities. It is a subtle shift, but vital in today’s commissioning climate.

Ross Harvie is Associate Director of Proteus Theatre Company Ltd.

www.proteustheatre.com

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.