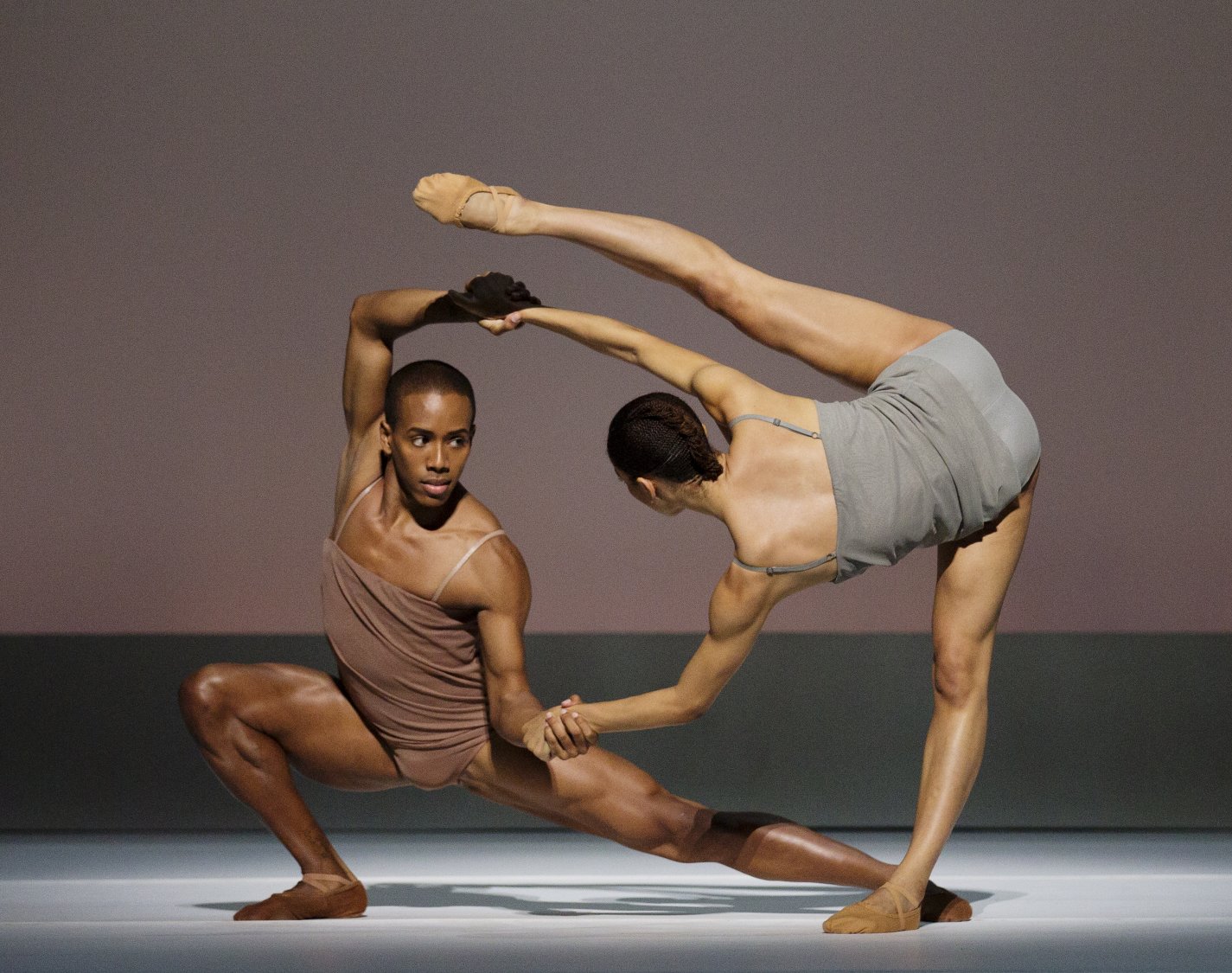

Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater’s Chroma by Wayne McGregor

Photo: Paul Kolnik

A call for a richer repertoire

David Jays explores the pressures on ballet's artistic directors who are frustrated by a narrow repertoire.

The feats of balance performed by dancers on stage are nothing compared to those facing the artistic director of a ballet company. Directors are torn between honouring the classics and fostering new talent. They want to push boundaries but balance the books. They hope to build new audiences without sacrificing existing fans. Especially in complex economic conditions, it is a recipe for sleepless nights.

I sensed these dilemmas when we canvassed opinion on the health of the ballet repertoire for Dance Gazette, the magazine of the Royal Academy of Dance (RAD). Six artistic directors of prestigious international companies on three continents were asked to name the ballets they would champion as recent classics, would rescue from neglect and, most provocatively, retire from the stage.

Everyone agreed that the repertoire is too narrow, especially when compared to theatre or opera

This last question really made feathers fly. Christopher Hampson of Scottish Ballet suggests that Swan Lake should be ‘semi-retired’, “so that companies [could] produce new works”. Assis Carreiro of the Royal Ballet of Flanders floated a radical five-year moratorium on the main Tchaikovsky ballets (Swan Lake, Nutcracker and Sleeping Beauty), in favour of original creations and neglected wonders. The reaction to these suggestions raged across social media and the national press, as balletomanes and commentators goggled at the prospect of losing Swan Lake. So why did the discussion touch a nerve?

Everyone agrees that the repertoire is too narrow, especially when compared to theatre or opera. Full-length narrative works especially are at a premium – as Karen Kain of National Ballet of Canada remarks: “Story ballets are the ones that keep ballet companies afloat.” In addition, David McAllister of Australian Ballet notes: “Many works have not survived due to the lack of reliable conservation methods. They relied on memory to be revived from generation to generation, and ballets that were not in constant performance died with the original creators.”

Other pressures squeezing the repertoire are inevitably financial. “It is very expensive to produce new unknown full evening ballets,” Carreiro acknowledges, “but we have a duty to the artform to ensure we are not simply archives of the past.” Without an impulse to innovate, she warns, it is no surprise that “companies are becoming more homogenous”. Demonstrating what is possible, Reid Anderson describes how generous subsidy and painstaking audience development at Stuttgart Ballet allow for "a wide diversity in our own repertoire which other companies, sadly, simply cannot afford”.

Even so, some recent works infiltrate the repertoire. Directors mention Wayne McGregor (especially ‘Chroma’, pictured above), Christopher Wheeldon (including ‘Alice’s Adventures in Wonderland’), Alexei Ratmansky and John Neumeier. Hampson advocates ‘Political Mother’ by Hofesh Shechter, which “really does something differently, but has a timeless message”.

We also canvassed suggestions for neglected pieces that deserve a revival. Several directors crave Anthony Tudor’s mid-century masterpieces like 'The Lilac Garden', 'Dark Elegies' and 'Pillar of Fire'. Carreiro also champions Agnes de Mille’s 'Fall River Legend' and 'Rodeo' (and wonders why no female artists were mentioned alongside Ratmansky or McGregor: “This is a huge issue”).

The most incendiary suggestion may not be about giving Tchaikovsky the elbow, but Tamara Rojo’s proposal for reviving the repertoire. “I would like the approach to be more like opera or theatre,” the English National Ballet director argues, “where the repertoire is consistently revived with a new vision and artistic direction that, sometimes, makes works wonderfully relevant and new.” Most companies stick with the same plush version of classics for decades, so the idea of constant renewal is bold.

But back to swans in peril. Reaction could not have been more vehement if directors had threatened to visit an RSPB sanctuary with an uzi. A headline version of the story on the RAD’s new website (cheekily titled ‘Swan Lake must die’) attracted scores of comments and an accompanying Twitterstorm. “It would be a mistake of the greatest magnitude to lose this heritage,” commented one reader. “I still choose to watch my favourite classics every year over newly created works,” said another.

Many commenters accept new ballets, but not at the expense of the classics. These works had converted hearts and minds to ballet in childhood. They kept people returning through adulthood, often with their own children. As far as many balletomanes are concerned, directors will have to prise the sugarplums from their cold dead hands.

You can read this reaction in two ways: Companies are sustained by their core audiences’ loyalty, but that same audience may hold them back. Rupert Christiansen takes a trenchant view in his Daily Telegraph arts column, he argues: “Ballet must wither if it can’t change and develop. The ‘hard-core fans’ who might support change aren’t sufficiently numerous to fill the house for anything different or innovative.” In a climate where the silent majority call the shots, and live cinema screenings supply top-flight artistry, he even suggests that English National Ballet and Birmingham Royal Ballet (BRB) should stop trying to push the envelope. Instead, Christiansen says, “They should give up the fight and only give Sunderland and Southampton the fairy tales that they want.”

Should we speak of a homogenous British ballet audience, or perhaps we have a range of audiences? Established classics fill the Royal Ballet, but so do triple bills with lower ticket prices – especially when they showcase international stars like Carlos Acosta or Natalia Osipova. BRB and Northern Ballet get a lot of love on home turf, but may struggle on tour. Meanwhile, below the critical radar, Russian classics with few pretensions schlep around the country.

So, is Christiansen right to question the prospects for renewing the ballet repertoire? I turn to someone on the sharp end of selling ballet: Laraine Penson, Director of Communications of Leeds-based Northern Ballet. The touring company specialises in narrative ballets, many by director David Nixon. Some are based on ballet classics, such as Swan Lake and The Nutcracker, others on familiar titles in other genres: Hamlet, Madame Butterfly and The Great Gatsby.

“Title is everything,” Penson says firmly. “Our audiences tell us they need to know they will understand the story.” Most of this discussion has implied that the ballet audience exists in a bubble, but marketing experts like Penson know this is not so: “We are a choice among many. Next time they might choose to see The Lion King, War Horse or Matthew Bourne. It’s more competitive than it’s ever been.” The Great Gatsby was a hit last year, buoyed by the flappermania around Baz Luhrman’s movie, but would it succeed again? “Our audiences more than ever are hungry for new works,” Penson says, “and we attract 50% of new audiences with every production.” The yen for novelty is as encouraging as the lack of loyalty might be dismaying.

Penson agrees she can’t take anything for granted: companies must win their audiences, production by production. “Part of it is about educating audiences – we do a lot now in direct mail, saying this is the story, these are the characters, showing them what they’re going to see on stage.” It isn’t merely about directors willing to take risks; the audience development that Stuttgart Ballet has pursued over five decades will, it seems, become increasingly important for companies who want to do more than keep the swan dancing.

David Jays is Editor of Dance Gazette.

www.rad.org.uk

@mrdavidjays

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.