Photo: Alan O'Rourke (CC BY 2.0)

The march of the Twitterati

Something fundamental is going on in the media world, says William Shaw. It’s big, scary, only half understood, and it’s going to change how the arts present themselves to the world.

In May this year, 80% of the UK online population visited an online social networking site – a dizzy four-fifths of everyone over 15 with an Internet connection. The UK now has 18 million active Facebook users – and that figure has been growing by almost 25% every three months. Compared to that, only around half of the UK population now even glance regularly a national newspaper. That figure is lower among 15–24 year-olds. Significant ideas are increasingly being communicated through social media, not through traditional means. We have been lectured so many times that the Internet is going to change everything that, like a lobster in a warming pot, we scarcely notice it now it’s happening. But we have reached a tipping point. The gap between what new and old media deliver is yawning. This changes how opinions are formed and how audiences are reached. It also raises interesting questions about where high quality criticism is going to come from in the future.

On the surface, there’s a simple conclusion to be reached from the arrival of the ‘Twitterati’. Arts organisations need to think more about social media. The Barbican website already has a social networks button to its front page. Fine idea. Twitter can fill empty seats within a couple of hours of a performance. But at the moment that’s where most people’s thinking stops. This is a mistake because the change is fundamental. Arts organisations, if big enough, used to hire press officers on the strength of their contacts book, but what does that mean now? It’s not just dipping circulations – accelerated by the recession, newspaper advertising revenues are expected to fall by as much as 21% across the board this year. This means cuts. Emails to old contacts suddenly bounce: they’ve gone freelance. Talent is leaching away from old media. The money spent trying to get column inches is increasingly money less well spent. This alone makes the move to using social media a necessity – but that’s just the half of it.

New tricks

Conventional arts websites have become good at doing two things. They list events coming up and maybe sell you tickets to them. If you’re lucky there’s a blog, but it’s often pretty thin fare. These sites exist within the fast-changing Internet filled with people sharing news, wit, opinion, photographs, films and music. In comparison, arts websites often look staid and monumental. They have more in common with the straight-backed world of thetrainline.com than the vibrantly creative environments they’re supposed to be reflecting. The key word is ‘sharing’. If arts websites want to move from the vertical model – telling people what’s good for them – to the horizontal model of using the energy of social networks, then it’s about giving stuff away. As any sociologist will tell you, the basis of any social network, real or virtual, is reciprocity. Arts organisations, increasingly strapped for cash, may balk at the idea of giving anything away, but a little imagination shows they sit on mountains of barely glimpsed riches.

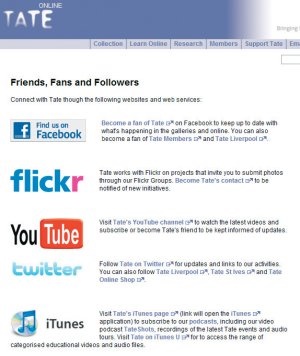

The real genius of this approach has been Will Gompertz, Director of Tate Media. You can happily spend hours lurking around Tate’s site, riffling through curators’ notes, lectures, podcasts, online magazines and archives. Excellent content elicits involvement. Few have Gompertz’s resources or cash. Instead we have to start thinking about the material our practice already produces that can enhance an audience’s understanding of what we do. Culture24’s website realised a long time ago what wealth was going to waste, and has been attempting to create a nationwide network by using the raw material that the arts produce as naturally as breathing, but it’s been an uphill job. We should be thinking: what do we have sitting on our shelves that can build profile and loyalty? It doesn’t have to cost the earth. It’s amazing what can be done with a £75 video camera and some editing freeware. Suddenly your web output starts to resemble a broadcasting channel, disseminating the material that seeds networks, pulling people towards you.

|

Difficult lessons

So the first lesson is that you have to become generous. That’s surprisingly difficult for some. Arts organisations have worked in much the same way as any commercial operation: never mention the opposition. In the new context, where everyone is talking about everyone else, that kind of behaviour appears sulky and aloof. What would happen if you started using your networks to praise great work by rival organisations – or even scarier – to say: “We could have done such-and-such a production better”? Wouldn’t that be great, though? Wouldn’t that encourage people to trust you more? The social web is a boundary-less place. The boundary that’s under greatest threat from new media is the one that keeps your audience at a safe distance. You have to think hard about what ownership they have over what you do. When a social network starts to rubbish the last exhibition you put on, do you ignore it? Do you react? Arts companies and artists have been used to having copy approval. How is that going to work within this looser model? There are no easy answers, but what you do as an organisation will be judged by how you deal with these questions. As new media writer Clay Shirkey says, good networks mean that institutions lose the power to control the agenda in the ways they are used to. The vertical gives way to the horizontal.

A new criticism

But that’s the really exciting part, too. This is where arts organisations can start to contribute something truly exciting to the way this new world develops. As the old institutions that supported arts critics wilt, can these new networks help to build a new approach in the way art is discussed? Can you imagine a world in which the headline quote praising the Young Vic’s latest production comes from an artist writing on Southbank Centre’s website? There is territory to be won. The point about networks is that when they are effective; when they share things of value, they are strong. And this is the big one: if the arts community embraces the new social networks in this spirit of generosity, it will become powerful. We’re approaching a new era in which arts are going to be threatened all round, so the arts are going to need the resilience these networks can provide.

William Shaw is a writer and Web Editor at the RSA Arts & Ecology Centre.

www..rsaartsandecology.org.uk

Join the Discussion

You must be logged in to post a comment.